Updated: Jan 24

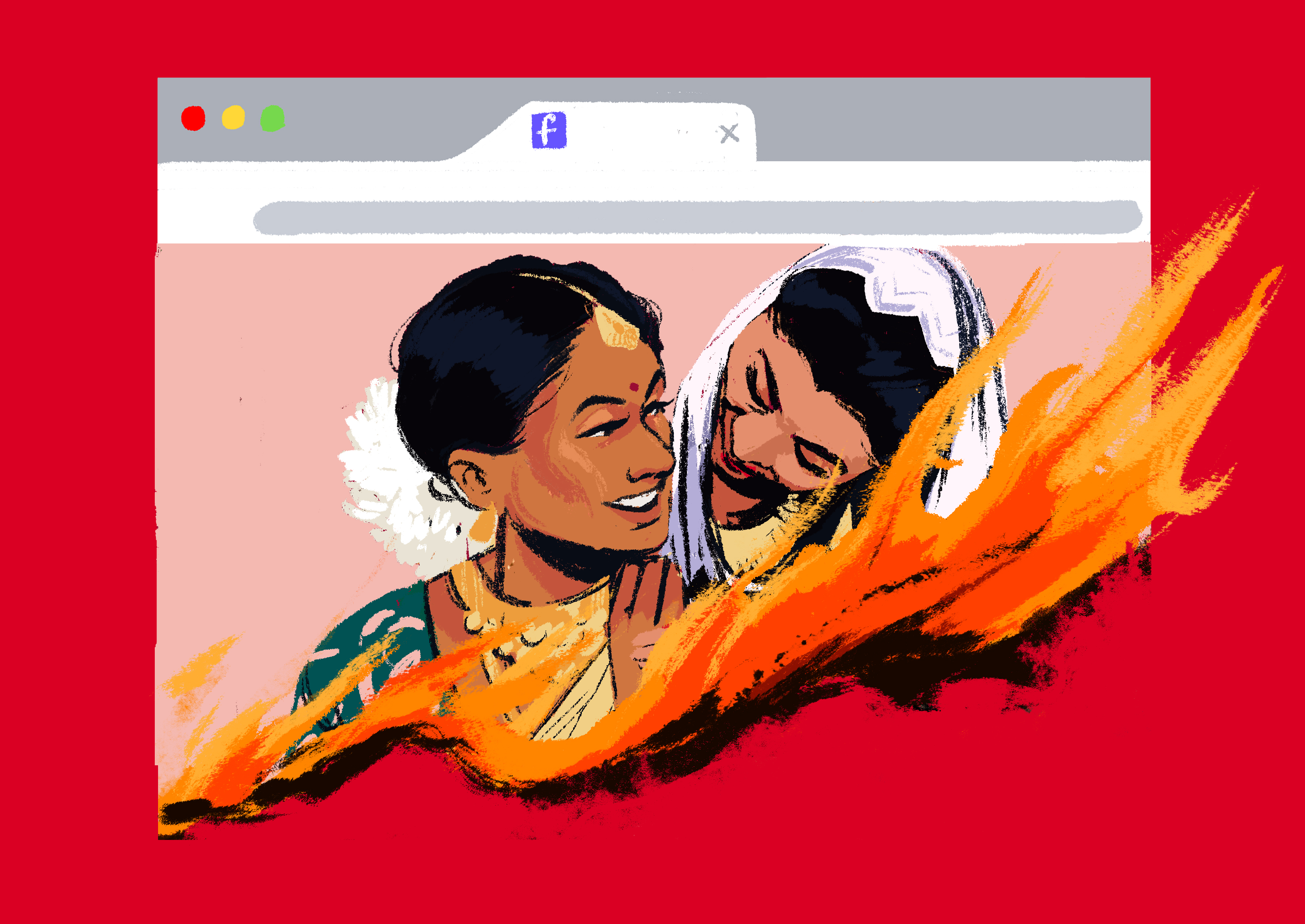

Clermont-Ferrand (France): On 14 October, less than 24 hours after Tata-owned jewellery brand Tanishq took down a festival season television advertisement in response to right-wing social-media outrage that its inter-faith theme promoted love jihad, Haryana-born artiste Kavi Singh posted a video message to her 250,000 followers on Facebook.

“A conspiracy is underway by those whose only interest is to increase their population, carry terrorism and spread filth,” she declared, explaining why the ad had to go.

On 12 and 13 October, the hashtag #BoycottTanishq was a top India trend on social media, fuelled by Hindu right-wing accounts. Comments about the television spot that depicted a Muslim household preparing to hold a Hindu ritual for a pregnant daughter-in-law quickly deteriorated into a communal rant, as live commentaries using the word "secular" as a pejorative (see below) blustered against polygamy and hijab-wearing.

Always sharply dressed in long-sleeved kurtas with a Modi jacket and colourful headgear, Kavi is a popular singer, belting out auto-tuned devotional and patriotic songs about Hindu deity Shiva, the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Indian soldiers and the Indian tricolour. But the 22-year-old also uses Facebook Live to deliver monologues on terrorism, a purported threat to India’s security from “communists and traitors” and protecting "Indian culture".

Days later, 25-year-old Yash Raj Singh of Patna in the northern state of Bihar conducted a Facebook live session claiming that ‘Hindu unity’ had dealt Tanishq a Rs 2,700-crore loss. “Hindu girls are forced to convert whereas Hindu boys are killed right away,” he said about ‘love jihad’, citing the example of Delhi teenager Rahul Rajput’s murder on 7 October, allegedly by a Muslim female friend’s family. Yash Raj has 60,000 digital supporters on his Facebook and Instagram accounts.

Kavi Singh and Yash Raj Singh’s Facebook activity is strikingly similar to hundreds of other accounts, public pages and groups that together form an inter-linked network of Hindutva groups on Facebook.

The self-proclaimed Hindutva leaders on these accounts are all minor-league players, but together they form a thriving web loosely connected to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), its ideological fountainhead the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and their affiliate organisations such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Bajrang Dal.

This web of social media accounts with tens of thousands of followers uses the world’s largest social media platform to dish out incendiary and communally charged content, strengthen an anti-Muslim narrative, drum up support for Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP, hail an aggressive militant Hindu identity, assert Hindu supremacy and champion a jingoistic nationalism. By their own accounts, these pages and groups are foot soldiers of the BJP’s Hindutva project working to realise a Hindu rashtra (country).

Even several levels removed from the BJP, this online cult of emerging Hindutva leaders benefits the ruling party’s politics, says Amarnath Amarsingam, professor at the School of Religion at Canada’s Queen's University and a scholar on religious extremism, political violence and their intersection on social media.

These players may be propaganda machinery, or distractors and noise-makers on non-issues, or used to spin unlikely narratives around an event to deflect criticism from the regime, he told Article 14. A recent example is the Hathras gangrape case, in which a fringe Hindutva group held demonstrations claiming that the upper caste Thakur community was being unfairly targeted.

“Historically, political powers wanting to distract people from real issues have latched on to communal identity to create a threat of the ‘other group’. They project a belief that politicians in rule are the only ones equipped to protect them,” Amarsingam said.

Even as international news organisations took note of the Tata group withdrawing the ad, Union Home Minister Amit Shah told News18 in an interview that he considered the right-wing outrage “over-activism”. He told the channel that the roots of Indian social harmony are strong, and that attacks by many including the colonial rulers and later the Congress party could not uproot them. Three days after the ad was withdrawn, the home minister said about the right-wing groups’ demand for it to be removed, “I believe there shouldn’t be any form of over-activism.”

Incidentally, he also appeared to gently chastise Maharashtra Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari who earlier in the week wrote to Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray criticising the government’s decision not to reopen temples and other places of worship yet. The Governor’s letter asked if the chief minister had “suddenly turned secular”. Shah told News18 that the governor could have chosen his words better.

Over the last five years, a rising tide of Facebook accounts and pages has worked to mobilise online support for offline communal violence, with lakhs of page-views and followers for their hate-speech and provocative posts.

These pages invoke Hindu deities Rama and Hanuman, and underline Islam as the enemy, their approach similar to the white supremacist groups on Facebook. Flooded with videos making false claims and fake news, these fall in step with other social media narratives towards the Hindutva project.

Facebook, for example, has not only faced criticism in recent times for partisan regulation of Indian political content, but an Article 14 investigation also showed that the company protected content linked to the BJP for more than a year, since before the 2019 general election to the Lok Sabha. Facebook failed to act against pages promoting the BJP’s agenda even though these functioned without disclosing their party affiliations, a requirement by Facebook’s own rules. Some of these pages were also Facebook’s largest advertising spenders.

More recently, Facebook pages that are part of this online right-wing network openly flouted Facebook’s policies on dangerous hate speech in posts about the anti-CAA protests. These pages egged on rioters who attacked protest sites, and called for violence in the Maujpur and Jafrabad localities of Delhi. Facebook failed to take these pages down, as reported by Article 14.

Responding to a detailed Article 14 questionnaire on the content of these Hindutva-espousing pages and groups, Facebook said it does not violate its community standards.

The company found two offensive comments on pages shared by Article 14 and removed those, it said. “We have a robust framework to assess groups and individuals that may be violating our Hate Speech and Violence & Incitement policies and we take action as appropriate,” said the official statement from Facebook. “While there is progress, we’re conscious that there’s more work to do.”

Facebook did not respond to specific questions about the content on these pages and groups but said the company had taken action globally against groups tied to violence or discussing potential violence, even if they used veiled language and symbols. According to the company’s statement, over the last three years, Facebook has “more than tripled” the number of people working on safety and security issues on the platform to more than 35,000, a global and multi-lingual team.

The Young, New Turks Of Online Hindutva

By his own account, 25-year old Yash Raj Singh of Patna is committed to establishing Hindutva, defined on his personal webpage as the ‘hegemony of Hindus’.

Few outside Bihar have heard of the Jehanabad-born Yash Raj, national president of the Bihar-based Shri Ram Seva Sangathan, but he aspires to sermonise to crowds of Hindus. He is also a proponent of affirmative action for savarna or upper-caste Hindus.

“Facebook has played a big role in my image as a Hindutva leader,” Yash Raj told Article 14 over the phone.

An 11-member team works on his social media accounts and web pages. He claims he gets death threats over the phone and in the comments section of Facebook, allegedly from irate Muslim social media users. He has on occasion recorded videos while purportedly answering such threat calls, and has posted them for his Facebook followers to view.

In March, as demonstrations against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 continued in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh and elsewhere, Yash Raj conducted a Facebook Live session, assuring the 27,000 viewers that a Hindu Rashtra, or Hindu nation, will be established in India. “If any untoward incident occurs on account of people from the other religion, I will not remain peaceful,” he said. A “conspiracy” to turn India into an Islamic nation is underway, he claimed during the live session.

Some of his videos have raked in more than 7,00,000 views.

Nearly 550 km west of Patna, in Lucknow, the capital of neighbouring Hindi heartland state Uttar Pradesh, Salabh Pratap Singh, is the founder-president of the Dharm Rakshak Sena, a Hindutva group that claims to have branches in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and the southern states. Usually photographed sporting a Che Guevara-style beret and sometimes waving a firearm, Singh was active in the 2018 protests against Bollywood film Padmavat by the upper-caste Rajput community’s Karni Sena.

Weeks into the nationwide lockdown to tackle the Covid-19 pandemic, Singh launched a drive in Lucknow to plant saffron flags identifying Hindu homes and establishments, in response to reports that a Tablighi Jamaat gathering in Delhi had been a super-spreader event. In June, he claimed he was the first Hindutva leader to be detained in Kashmir for attempting to unfurl a saffron flag at Lal Chowk, Srinagar.

His Facebook account bears video clips of him threatening to attack Muslims if they insult Hinduism or indulge in ‘love jihad’, a right-wing coinage to refer to inter-religious relationships. In a clip posted on 19 May, he is seen telling local news reporters that the Dharm Rakshak Sena will pick up arms against those who insult Hinduism.

Facebook posts by Salabh Singh and Yash Raj Singh, and by dozens of self-styled leaders of obscure Hindu groups across the country, are shared and amplified on other Facebook pages bearing names such as Ek Kadam Hindu Rashtra ki Aur (A Step Towards A Hindu Nation, with 1.1 million members) Kattar Hindu Group (Extremist Hindu Group, 5,56,000 members), Bajrang Dal Mein Kattar Hindu Jude (Inviting Extremist Hindus Into The Bajrang Dal, with 80,000 members), Yogi Adityanath ki Sena—Hindutva Ke Liye Jude (Yogi’s Army - Join For Hindutva, with 41,000 members).

Nilanjan Sircar, senior visiting fellow at Delhi-based Centre for Political Research, told Article 14 that there is an explicit offline market for such social media content, “an audience that is drawing huge viewership and consuming this packaged information and spreading it further in the population”.

Sircar, who studies comparative political behaviour and social network analysis among other topics, said the social media ecosystem of Hindutva groups complements advocacy for their offline activities and ideology.

Article 14 asked the RSS if it supports or condones the content on these pages and groups claiming to espouse its cause or are inspired by the Sangh. RSS joint general secretary Manmohan Vaidya said while anyone can form such groups in the name of the Sangh, they don’t represent the organisation’s official views.

On the Tanishq ad, however, RSS' Vaidya said, “Love jihad has been rampantly spreading in India in recent years, and there is a pattern of trapping Hindu women who are then forced to convert and eat cow-meat by men hiding their Muslim identity.”

He added that “Hindu samaj” (the community) is not restricted to the RSS, and that people have a right to express opinions and they did so by objecting to the ad.

Saffron Kits And Tridents, Recruitment And Radicalisation

Article 14 found at least 30 individual accounts, official pages and public groups with this hardline Hindutva flavour. They have followers ranging from 10,000 to more than 1 million.

In September, multiple accounts posted recruitment calls for the Rashtriya Bajrang Dal (RBD), part of the Antarrashtriya Hindu Parishad (AHP, literally translated as international Hindu council), launched in 2017 by former VHP chief Pravin Togadia. The post assured every new member a gift — a pocket-sized metal trident, a weapon wielded by deities in the Hindu pantheon.

This post was published on a public group named RSS Samarthak (‘RSS Supporters’, with 89,000 followers) and I Support Namo, a private group with 9,29,000 members and Hindu Rashtra Bharat, a page liked by 94,000 people. The page admins did not respond to attempts by Article 14 to verify details of the membership drive.

The Bhagwa Swayamsevak Sangh (BSS) headed by a man named Suresh Norva also launched a membership drive on its Facebook page, in September. Formed in 2015, the outfit works to protect “Gau-Garib-Kisan-Rashtra-Maa-Behen” (cows, poor people, farmers, nation, mothers and sisters), according to Norva. He said he hopes to expand the organisation’s reach from its current location in Jaipur in the western state of Rajasthan. The BSS said it will hand out a saffron kit of sorts to members, including an identification card, a saffron t-shirt, a flag and a windshield sticker in the shape of the outfit’s symbol, a bow and arrow.

Yash Raj and Salabh Singh, among others, are also inviting members into their organisations. All of these continue the trend of Hindutva groups leading the charge in using the Internet to disseminate their ideology, as noted by experts (here and here).

From these 30 groups and pages, it emerges that Facebook and its platforms are an attractive medium for Hindu groups in non-urban areas or in mofussil towns, the social media behemoth growing their reach exponentially. Almost a third of India’s electorate uses Facebook and WhatsApp, according to this Lokniti study.

As inexpensive smartphones and cheaper mobile data packs proliferated over the last five years, social media has been democratised, giving wider space to non-English speaking communities. This continued a process that began with the BJP’s rise to power in 2014, since when fringe elements have stepped out of the shadows of larger Hindu organisations.

“The Hindutva movement was on the fringe for the longest time. But Facebook and social media have been a godsend for people in such groups wanting to organise or have their voices heard,” said Hari Prasad, a research associate at the Washington-based Critica Research. “Social media provides an arena to send out their message easily, cheaply, and they use it to try and dominate the narrative.”

Prasad said online trends show the emergence of a new generation of tech-savvy Hindutvawadi (Hindutva believers) leaders from the grassroots. With social-media platforms such as Facebook, new local leadership can emerge easily, a great opportunity “for folks who want to elevate their own clout”.

Being identified as a hardline Hindu is seen as a ticket to greater political clout.

Manish Yadav is a small-time political leader in Lucknow who quit the Samajwadi Party in 2018 after a five-year stint and adopted the Hindutva cause. The 24-year old caused a stir in January when posters with his face and the message ‘Jaago Hindu, Jaago’ (wake up, Hindus) made an appearance in Lucknow, under the banner of the ‘Hindu Army’, an outfit he floated to protect ‘oppressed’ Hindus against a backdrop of anti-CAA agitations countrywide.

In February, the Lucknow police booked him under Sections 153-A and 505 (2) of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, for promoting enmity between groups, and under Sections 66 and 67 of the Information Technology Act, 2000, for publishing obscene material. In a video clip dated 27 February, following riots in north-eastern Delhi, Yadav threatened to make Delhi Islam-free if the government gave him a free hand.

Yadav now promotes himself on Facebook as chief of the Hindu Army, a page that has 1,36,000 followers. In August, he launched the Krishna Janmabhoomi campaign on Facebook and headed to Mathura, the Uttar Pradesh city that is the mythological birthplace of Hindu god Krishna. He said he would “liberate Lord Krishna’s birthplace”.

The Mathura police on 22 September arrested Yadav and 22 activists for trying to disturb the peace. On 30 September, a Mathura civil court dismissed a suit seeking the removal of encroachments and the Shahi Idgah mosque built on the purported Krishna Janmabhoomi plot. On 16 October, a district court in Mathura admitted another plea seeking the removal of the 17th century Shahi Idgah mosque from the 13-acre property.

On his official Facebook page, Yadav has said his outfit fights for “nyay aur dharm” (justice and religion), and that they won’t hesitate to “pick up weapons”. Yadav’s next battle will be for a “population control bill that will open the doors for the realisation of a Hindu Rashtra”.

Online Posts Spur Offline Violence

These right-wing networks on Facebook are replete with suggestions to followers to keep weapons in their households, and to prepare for the battle for Hindutva.

On 30 January, 17-year-old Ramgopal Bhakt fired shots from a country-made pistol in the direction of a crowd of anti-CAA protestors outside Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia University, in full view of policemen and journalists. He injured one protestor. Before arriving at the spot, he meticulously explained his actions on his Facebook profile.

A Bajrang Dal member, Ramgopal’s Facebook posts from October 2019 onwards offered an intimate glimpse into his evolving radical mind: profile images of him kissing a sword, wearing saffron clothes, posing with union minister Giriraj Singh and other right-wing Hindutva activists.

Ramgopal was apparently inspired by Union Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur’s’ poll slogan ‘desh ke gaddaron ko, goli maaro saalon ko’ (shoot the traitors) raised just two days earlier. He travelled 67 km from his home in Jewar near Noida, to Jamia in south Delhi, to exhibit his anger against the sit-in anti-CAA protests. “Shaheen Bagh, khel khatam,” (game over), he wrote on Facebook. He posted 17 live videos within three hours, and urged his followers to stay glued to his FB page as he approached the site of the incident.

“I am the lone Hindu here,” he wrote in a post explaining his search for revenge after the death of Chandan Gupta, a youth killed in Uttar Pradesh four days earlier, allegedly for participating in a ‘tiranga yatra’ (tricolour march) on India’s Republic Day. Young Hindus are murdered for displaying their nationalism, he raved.

Less than two hours after the attack, Facebook deactivated the account. A spokesperson said there would be no place on the social media platform for such acts of violence. Facebook also removed content that praised or supported Ramgopal.

The Hindu Putra Sangathan’s chief Rajeev Brahmarshi, known as ‘Bihar’s Thackeray’ for imitating the fiery oratory of the late founder of the Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, has had at least six different Facebook accounts permanently banned since 2017, upon the state government’s requests.

“There is no doubt that Facebook has helped to further my political career,” Brahmarshi told Article 14. He continues to stay on Facebook through multiple new accounts with his 2.5 lakh followers.

He conceded that many Hindu leaders post incendiary content on Facebook, chasing a larger fan following. He claimed he did not cross that line, but last December, the Hindu Putra Sangathan, Bajrang Dal and other Hindu-nationalist outfits organised a rally in Patna to support the CAA, preceded by an inflammatory speech posted on 19 December by Brahmarshi.

Brahmarshi warned anti-CAA protestors: “These infertile, jihadi infiltrators coming from Kashmir have made a big camp in India… We call them a minority but you must have realised their power by now.” Nagesh Samrat, a colleague in his outfit, posted a 10-second TikTok clip on his Facebook page, warning protestors not to complain if “Godhra returns”, referring to the 2002 Gujarat riots. These videos are still present on their accounts.

The atmosphere at the Patna rally was charged. As it traversed the Muslim-dominated Haroon Nagar locality of Phulwari Sharif, there was stone-pelting and clashes. Samrat and seven others were arrested on 3 January by Bihar police on charges of murdering an 18-year old anti-CAA protestor who disappeared after attending the protests. The Wire reported it to be the first documented instance of “an anti-CAA protestor falling victim to violent reprisals by Hindutva groups”.

Brahmarshi attempted self-immolation in front of the Bihar Police headquarters on 20 February. This episode, as well as his arrest, was captured on Facebook Live.

With social media, Ramgopal, Brahmarshi, Yash Raj, Kavi Singh, Norva and others no longer need to wait on mainstream media for coverage. While Whatsapp’s encryption settings offer anonymity for rumour-mongering or fake news, these self-styled Hindu leaders use Facebook Live to be seen and heard.

Growing Facebook Popularity For Offline Visibility

Yash Raj from Bihar told Article 14 that he records his commentary on issues requested by followers, intervenes in local crimes and highlights issues that he feels need attention.

“But I receive maximum likes for videos on Islam, although I don’t support violence or extremism towards the community,” he said. “I want to work on issues that will take the cause of Hindutva forward.”

Figures like Yash Raj are on Facebook for visibility, said journalist Mohammad Ali who has reported (here, here and here) on right-wing Hindu groups in the Hindi heartland.

“And there is still no action against many of them by the police or Facebook.” He said these leaders are aware that communally charged statements yield higher online traction.

These new age leaders are not truly independent, but work in an organised manner, tethered to the larger network of the BJP and the Sangh. Their local influence translates into political muscle power too.

“The RSS and the BJP are not ignorant of such characters. They keep an eye on them. They groom such people and they know exactly when to use them,” said Ali, who chronicled the rise of a Hindutva leader named Vivek Premi who went from being a Bajrang Dal activist to Shamli district chief of the BJP.

Premi shot to fame when he assaulted a Muslim man on suspicion of cattle smuggling, in June 2015. Premi set up his Facebook page during his subsequent prison stint, Ali said. “They receive their messaging from the top-down command. There is legitimacy to the hate-speeches and violent threats delivered and they know that down the line, they will be rewarded for it.”

On quieter days, these groups and leaders mobilise grassroots support. With Covid-19 restrictions in place, much of the campaigning for the Bihar Assembly elections will be digital, and Facebook and Facebook-owned WhatsApp will be central.

The BJP has appointed 9,500 IT cell heads and as many as 72,000 WhatsApp groups in Bihar, while the ruling Janta Dal (United) has established 53 Facebook pages, Facebook Live programmes called ‘Sunday Samvad’ and Whatsapp groups connecting booth-level workers with the district, state and national leadership.

Yash Raj and Brahmarshi of Patna said they are not making a foray into politics, for now. But they are open to aligning their support base with leaders or groups seeking their support. “Whichever party talks of advancing the cause of Hindutva, I will support them,” Yash Raj said.

(Shweta Desai is an independent Indian journalist and researcher based in France)

Previously on Article 14:

The Hateful Facebook Adventures Of Ragini Tiwari & Friends

Online Groups Stoked Anger Over Sushant Singh Rajput's Death