Uttar Pradesh (UP): At least 11 Supreme Court rulings over 10 months granting bail appear to be gradually reshaping bail jurisprudence in India, especially with regard to India’s terrorism and money laundering laws.

The restrictive bail provisions of these laws have been frequently used to keep accused, mostly protestors, poets, Opposition politicians, dissidents, academics and artists, in jail with no sign of trial.

The main laws used to restrict bail are the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA 1967, and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) 2002, which many have often held as violating personal liberty enshrined in Article 21 and Part III of the Indian Constitution

Under India’s criminal law system, bail is supposed to be the rule and jail the exception, but judges have often quoted statutory provisions of restrictive laws, such as section 45 of the PMLA and section 43D(5) of the UAPA, to deny bail whenever law-enforcement agencies have invoked these sections.

In Prem Prakash vs Union of India, a Supreme Court bench of Justices B R Gavai and K V Viswanathan said on 28 August 2024, “Where the accused has already been in custody for a considerable number of months and there being no likelihood of conclusion of trial within a short span, section 45 of PMLA can be suitably relaxed to afford conditional liberty.”

One decision often affects the next.

In its latest bail order, on 2 September 2024, when the Supreme Court held that liberty was “sacrosanct” and freed Vijay Nair, a former communications head of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) after 23 months of incarceration in a PMLA case, it referred to the order of Justice Gavai’s bench.

The same day, another Supreme Court bench of justices Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan granted bail to another AAP member, Bibhav Kumar, a close aide of incarcerated chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, who, however, continues to be in jail for 165 days after getting bail in a PMLA case but swiftly arrested in another case, hours before the Supreme Court was set to hear his petition against the Delhi High Court order staying bail granted by trial court.

On 27 August, a Supreme Court bench of Justices Gavai and K V Viswanathan granted bail to Bharat Rashtra Samithi leader K Kavitha in a money laundering and corruption case related to an award of liquor contracts in Delhi, questioning the fairness of the prosecution agencies and criticised their “selective approach” in treating some accused as approvers.

On 30 August 2024, a bench led by Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud granted bail to Mukesh Salaam, accused under the UAPA over alleged links with Maoists in Chhattisgarh, taking into account the fact that he had been under custody since 6 May 2020, with no likelihood of an early conclusion to the trial.

Other recent bail orders led to freedom for prominent accused, such as Jharkhand chief minister Hemant Soren who was granted bail by the Jharkhand High Court on 28 June, confirmed by the Supreme Court a day later after five months in jail; Delhi deputy chief minister Manish Sisodia after 17 months in jail; and Prabir Purkayastha, founder of NewsClick, a website, after seven months in jail; and several others.

The decisions of the Supreme Court in Prem Prakash vs Union of India in August 2024, Pankaj Bansal vs Union of India in October 2023, Prabir Purkayastha vs State (NCT of Delhi) in May 2024, Javed Gulam Shaikh vs State of Maharashtra in July 2024, Sheikh Javed vs State of UP in July 2024, Jalaluddin Khan vs Union of India in August 2024 and five other cases signify a shift—after periods of long incarcerations on allegations by law-enforcement agencies—towards an approach where bail is increasingly seen as the norm rather than the exception.

It would be fair to say that these landmark judgements appear to be setting a trend of sorts, but it is too early to say if they indicate an overhaul in bail jurisprudence, given the number of prominent dissidents, activists, academics and singers who remain incarcerated.

No Signs Of An Overhaul

Several other undertrials or accused remain in jail with no signs of a trial, their cases revealing how, even as the Supreme Court makes bail a more urgent issue, it has gone against its own observations in other high-profile cases, all important to government allegations of conspiracies.

Some examples:

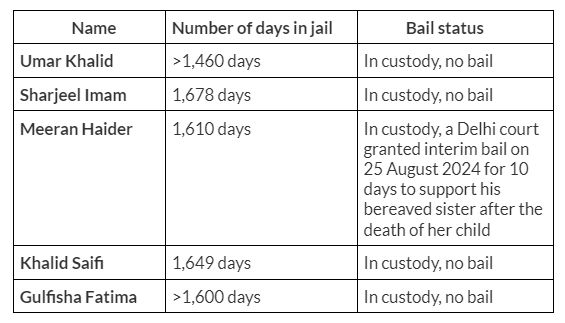

- There is no sign of a trial, but numerous bail hearings and four years have passed for activist Umar Khalid, his bail application adjourned 13 times in the Supreme Court alone, before being withdrawn

- It’s been four years for former software engineer turned history student Sharjeel Imam, imprisoned like Khalid in the Delhi riots conspiracy case, charged under the UAPA for a speech he made

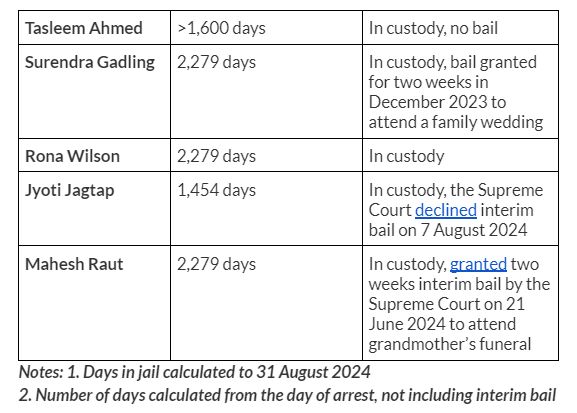

- In the equally infamous Bhima-Koregaon case, singer Jyoti Jagtap has also spent almost four years in jail, denied bail on 22 August 2024 by the Supreme Court

- It’s been six years for activist and researcher Rona Wilson, his bail application most recently rejected on 26 July 2024 by the Bombay High Court in the Bhima-Koregaon case

- It’s been more than six years in jail for former Adivasi activist Mahesh Raut, whose bail plea the Supreme Court has not heard for a year after staying a high court grant of bail

Supreme Court judgements that prioritise Article 21 of the Constitution, the right to life and liberty, over everything else, even in UAPA and PMLA cases, appear to be ignored when it comes to those accused in the Delhi riots conspiracy case and the Bhima-Koregaon cases.

Several Delhi sessions court judges have at various times described investigations into the Delhi riots conspiracy case as “absolutely evasive,” “lackadaisical,” “callous,” “casual,” “farcical,” "painful to see,” and “misusing the judicial system”.

Judges have dismissed at least 60 Delhi riots cases over four years, the latest in March 2024, with the judge saying police statements were “artificially prepared”, as Article 14 reported in May 2024. The police have claimed this case was one of those that sparked the riots in March 2020, in which three-quarters of those killed were Muslim.

Eighteen of the 20 accused of planning the violence are Muslim, including Khalid and Imam. Article 14 reported in December 2023 that nine accused in the Delhi riots case, eight men and a woman, all Muslim, remain in jail after lower courts denied bail. Their petitions challenging bail denial have also been pending for between 11 to 19 months in the Delhi High Court.

In the Bhima-Koregaon case—which, as Article 14 reported in May 2022, changed from speeches inciting violence at a Dalit gathering in 2018 to allegations of an assassination attempt against Prime Minister Narendra Modi to a Maoist conspiracy to overthrow the government—seven of 16 are on bail, and nine remain in jail, including Raut and Jagtap, facing charges under the UAPA.

As regards the PMLA, while some have been released, there are few signs of larger constitutional issues around the use or misuse of the law being addressed by the Supreme Court, as Article 14 reported in July 2024.

No Urgency In PMLA Issues

Compared to the previous government led by the Indian National Congress between 2004 and 2014, there was a four-fold jump in cases filed by the Enforcement Directorate (ED)—the enforcing agency for PMLA cases—against politicians under the coalition led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) between 2014 and 2022.

An investigation by The Indian Express revealed that 95% or 115 or 121 prominent politicians against whom the ED filed cases, raided or questioned between 2014 and September 2022 were from the Opposition. Only 25 or 0.42% of 5,906 cases registered until January 2023 had been concluded.

More than 16 months after Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud refused to entertain a petition filed by 14 Opposition parties alleging “arbitrary use” of the ED but said his court could “evolve general principles with respect to the facts” of the case, at least three pending challenges to the PMLA have not been listed for hearing.

One of those is a review petition against a July 2022 Supreme Court judgement that upheld the constitutionality of various PMLA sections.

A three-judge bench headed by Justice A M Khanwilkar, who is now India’s Lokpal or anti-corruption ombudsman, had upheld some of the most controversial ED powers relating to arrest, search and seizure of property without filing a first information report (FIR).

The Supreme Court court in that case did not investigate the government’s claims that money laundering was akin to terrorism, turned the burden of proof to the accused, and handed to the ED a slew of extraordinary powers—more than any police force—to strike down individual liberties, lawyers Stuti Rai and Harini Raghupathy wrote in 2022 in Article 14.

Several review petitions filed against what is known as the Vijay Madanlal judgement were listed for hearing for the first time on 6 August 2024, more than two years after notices for hearings were issued on 25 August 2022.

The Supreme Court has tentatively listed the review petitions on 18 September 2024.

In 2017, a bench of Justices Rohinton F Nariman and S K Kaul held that moving the burden of proof on the accused was unconstitutional. But the union government reintroduced this condition through an amendment to the PMLA in 2018.

Yet, the reasoning used in a slew of recent cases by the Supreme Court in granting bail to those accused under the UAPA and the PMLA indicate an evolving jurisprudence, one that has largely been absent thus far.

Restructuring Bail Jurisprudence

Section 45 of the PMLA says bail can only be granted if a court is convinced that there are "reasonable grounds" to believe that the accused has not committed the offence and is not likely to commit any offence while on bail, called the ‘twin conditions’ of bail.

Similarly, section 43D(5) of the UAPA restricts the granting of bail if there are "reasonable grounds" to believe that the accused is prima facie guilty. In 2020, Article 14 had analysed these legal processes and explained how the restrictive provisions of this section ensures that the proof of innocence or guilt is rendered irrelevant.

Here’s how recent Supreme Court judgements are restructuring or watering down these restrictions:

1. Pankaj Bansal vs Union of India: On 13 October 2023, the Supreme Court held that an arrest made by the ED without providing written grounds of arrest to the accused person violated Article 22(1) of the Indian Constitution. The Court said it was not satisfied with the ED reading out the grounds of arrest to the accused, instead of providing it in writing.

“... a person who has just been arrested would not be in a calm and collected frame of mind and may be utterly incapable of remembering the contents of the grounds of arrest read by or read out to him/her. The very purpose of this constitutional and statutory protection would be rendered nugatory by permitting the authorities concerned to merely read out or permit reading of the grounds of arrest, irrespective of their length and detail, and claim due compliance with the constitutional requirement under Article 22(1) and the statutory mandate under section 19(1) of the Act of 2002.”

2. Prabir Purkayastha vs State (NCT of Delhi): On 15 May 2024, the Supreme Court ordered the release of Purkayastha, noting that the Delhi Police had not provided the written grounds for arrest and so had not complied with the Pankaj Bansal judgement. The Court distinguished between “reasons for arrest” and “grounds of arrest”, emphasising that:

“... the grounds of arrest informed in writing must convey to the arrested accused all basic facts on which he was being arrested so as to provide him an opportunity of defending himself against custodial remand and to seek bail. Thus, the ‘grounds of arrest’ would invariably be personal to the accused and cannot be equated with the ‘reasons of arrest’ which are general in nature. From the detailed analysis made above, there is no hesitation in the mind of the Court to reach to a conclusion that the copy of the remand application in the purported exercise of communication of the grounds of arrest in writing was not provided to the accused appellant or his counsel before passing of the order of remand dated 4th October, 2023 which vitiates the arrest and subsequent remand of the appellant.”

3. Javed Gulam Nabi Shaikh vs State of Maharashtra:This was the case that marked Supreme Court restructuring of bail jurisprudence in special statutes. On 3 July 2024, in granting bail to Shaikh, in custody since February 2020 for alleged smuggling of counterfeit Indian currencies from Pakistan, the Supreme Court held that however serious a crime may be, an accused has a constitutional right to a speedy trial:

“If the State or any prosecuting agency including the court concerned has no wherewithal to provide or protect the fundamental right of an accused to have a speedy trial as enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution then the State or any other prosecuting agency should not oppose the plea for bail on the ground that the crime committed is serious. Article 21 of the Constitution applies irrespective of the nature of the crime. We may hasten to add that the petitioner is still an accused; not a convict. The overarching postulate of criminal jurisprudence that an accused is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty cannot be brushed aside lightly, howsoever stringent the penal law may be.”

4. Sheikh Javed Iqbal vs State of Uttar Pradesh: On 18 July 2024, the Supreme Court widened the principle laid down in the Javed Gulam Nabi Shaikh case. The Court, in granting bail to UAPA accused Iqbal, noted that despite the seriousness of the charges, the slow progress of the trial, with only two witnesses examined over nine years of detention, weighed heavily in favour of bail.

“A constitutional court cannot be restrained from granting bail to an accused on account of restrictive statutory provisions in a penal statute if it finds that the right of the accused-undertrial under Article 21 of the Constitution of India has been infringed. In that event, such statutory restrictions would not come in the way. Even in the case of interpretation of a penal statute, howsoever stringent it may be, a constitutional court has to lean in favour of constitutionalism and the rule of law of which liberty is an intrinsic part.”

5. Frank Vitus vs Narcotics Control Bureau: On 8 July 2024, the Supreme Court held that there cannot be a bail condition that enabled the police to constantly track the movements and violate privacy of the accused. A bench of Justices Abhay S Oka and Ujjal Bhuyan considered if a bail condition requiring an accused to send a Google map pin to the investigating officer violated privacy.

6. Jalaluddin Khan vs Union of India: On 13 August 2024, the Supreme Court said if conditions for bail were met it could be granted even if special statutes, such as the UAPA, were used. Imprisoned for almost two years, Khan was accused of renting out his property to the banned organisation Popular Front of India (PFI), allegedly for training.

“The allegations of the prosecution may be very serious. But, the duty of the Courts is to consider the case for grant of bail in accordance with the law. “Bail is the rule and jail is an exception” is a settled law. Even in a case like the present case where there are stringent conditions for the grant of bail in the relevant statutes, the same rule holds good with only modification that the bail can be granted if the conditions in the statute are satisfied. The rule also means that once a case is made out for the grant of bail, the Court cannot decline to grant bail. If the Courts start denying bail in deserving cases, it will be a violation of the rights guaranteed under Article 21 of our Constitution.”

7. Manish Sisodia vs Directorate of Enforcement: On 9 August 2024, the Supreme Court granted bail to former Delhi deputy chief minister Sisodia on 9 August 2024, accused of corruption in granting liquor contracts. The Court said trial and high courts appeared to have forgotten the principle, 'bail is the rule, jail an exception'.

"From our experience, we can say that it appears that the trial Courts and the High Courts attempt to play safe in the matters of grant of bail. The principle that bail is a rule and refusal an exception is at times followed in breach...on account of non-grant of bail, even in open-and-shut cases, this court is getting a huge number of bail petitions thereby adding to the huge pendency. It is high time that the trial Courts and the high Courts should recognise that bail is the rule and jail an exception"

8. Prem Prakash vs Union of India through the Directorate of Enforcement: On 28 August 2024, the Supreme Court reiterated that bail was the rule even in PMLA cases, allowing bail to Prakash, accused of money laundering. The Court said section 45 of the PMLA only laid down that the grant of the bail would be subject to the twin conditions and do

For those who stay in jail, however, these principles have not been applied.

Supreme Court Vs Its Own Orders

This table makes clear how a number of prominent prisoners have not received the benefit of the Supreme Court’s evolving bail-not-jail jurisprudence.

In many of these cases, the Supreme Court has gone against its own observations by deferring bail hearings.

For instance, in the case of activist Imam, the case came up at least 60 times before the Court. In Fatima’s case, bail has been listed at least 64 times. In Khalid Saifi’s case, advocate Rebecca John informed the Delhi High Court that no charges had been framed even after four years.

Consider the case of Raut, arrested in June 2018. After more than five years, the Bombay High Court on 21 September 2023 granted bail in the Bhima Koregaon case, observing that there, prima facie, was no evidence against him to attract UAPA offences, noting he had spent five years and three months in jail without trial. Yet, the Court kept the bail order in abeyance for a week, so the National Investigation Agency could appeal it in the Supreme Court.

On 27 September 2023, the Supreme Court not only stayed his release but extended stay the week-long stay granted by the Bombay High Court on the bail order, till the next date of hearing, which was 5 October 2023.

Such continuing incarcerations of those accused of supposed crime offer contrasts with others convicted of serious crimes.

Selective Justice: The Ram Rahim Case

The Delhi riots conspiracy case has often sparked questions have been raised about the manner in which the Delhi High Court is handling the bail petitions of those accused in the Delhi riots larger conspiracy case.

In July 2024, Justice Anup Jairam Bhambhani of the Delhi High Court said the investigation into the death of a 23-year-old called Faizan—who died during the Delhi riots after being beaten by police who forced him to sing the national anthem—had been “tardy and sketchy” and “conveniently sparing” of those involved in “brutally assaulting” him.

“The case presents allegations of gross violation of human rights, as the unlawful actions of the policemen, who are yet to be identified, were motivated and driven by religious bigotry and therefore would amount to a hate-crime,” said Justice Bhambani.

Contrast such investigation and incarcerations of others in the Delhi riots and Bhima-Koregaon cases with the case of Ram Rahim, granted seven paroles or releases from jail over10 months to June 2024, despite currently serving a 20-year jail term for raping two disciples.

In January 2024, Rahim was granted a 50-day parole, following a 21-day furlough in November 2023, his third temporary release in 2023 alone. He was allowed a 30-day parole in July 2023, a 40-day parole in January 2023, and a 40-day parole in October 2022.

Those are just some periods of freedom that courts have granted a man who was also convicted in 2021 for planning a murder. In 2019, he was convicted for the murder of a journalist.

The Delhi riots and Bhima-Koregaon cases have at least gained some publicity. Many undertrials stay in jail unknown and certainly do not enjoy the freedom that Rahim has.

The Chief Justice Chadrachud said in July 2024 that trial courts, often, hesitated to grant bail in UAPA cases, continuing to prioritise the strict requirements of special statutes over the fundamental right to liberty, but there is ample evidence that his court, despite the recent cases, has some way to go in following its own observations.

(Areeb Uddin Ahmed is an advocate practising at the Allahabad High Court.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.