Hyderabad: After the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and National Population Register (NPR), there is the National Register of Vehicles, Vahan, which poses a potential threat to the assets of Muslims and other minorities in India.

The Vahan database and m-parivahan mobile application allows anyone to search the details of motor vehicle ownership in India. There are claims (here and here) of Vahan databases and mobile applications being used to target Muslim vehicles in the on-going Delhi riots.

Vahan and its sister database Sarathi—a national register of driving licenses—were built as part of the National e-Governance Plan. Part of the 11th five-year plan to help improve service delivery to citizens, Vahan and Sarathi are not only databases but they provide Regional Transport Office (RTO) services like registration and obtaining licenses. As part of these services, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways publishes, sells vehicle-registration data and license information to insurance firms, banks and entities into micro-finance.

The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways earned Rs 65 crore selling this information, according to a parliamentary question answered by the minister on 8 July 2019. As many as 142 companies have access to this data, according to a September 2019 RTI reply from the ministry.

Individuals and lawyers have raised concerns (here and here) about the sale of personal data and how the ministry is publishing it without consent. The practice of selling RTO data is not new, but publishing the data at this scale allows any business and mobile application developer in the country to have this data.

The government position on privacy was made clear when it contended that privacy is not a fundamental right guaranteed under the constitution.

The Rise Of National Registers

The rise of national registers in India occurred in the backdrop of the Mumbai attacks of 26/11 in 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the US. The economic survey of 2018-19 puts on record the government’s ambition to sell personal data from government databases, an idea first pushed into governance with Aadhaar and IndiaStack: “The principle is that most data are generated by the people, of the people and should be used for the people. Enabling the sharing of information across datasets would improve the delivery of social welfare, empower people to make better decisions, and democratize an important public good.”

The economic interest in personal data is evident with the push to collect information, but how is it used or from where does the industry collect this information?

Several fintech firms have crawled this information from the national Vahan websites or from state government websites that also publish this information. These firms use this data to provide backend services for asset verification for car loans and microfinance.

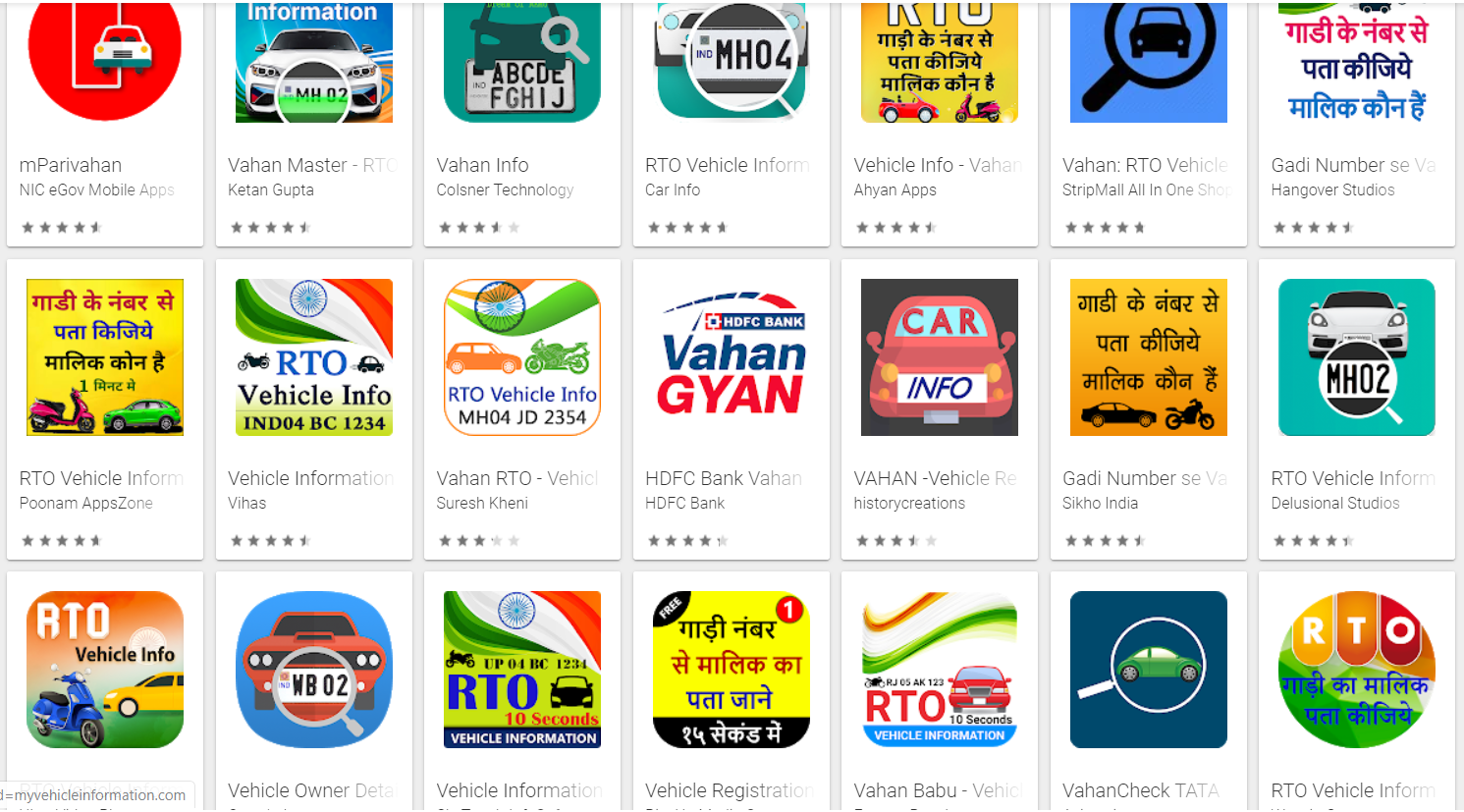

The proliferation of Vahan data is so huge that Google’s Play Store is full of mobile applications from random developers with this data. These companies do not have the right to possess this information without individual consent, but the ministry of road transport encourages the use of this data by selling it in bulk to any Indian firm which can pay Rs 3 crore. Several state Vahan websites have published Aadhaar numbers of car owners too publicly at some point of time until they were asked to remove them.

This kind of publication and proliferation of data is dangerous.

The case of rioters using Vahan to attack cars owned by Muslims is one such scenario. Insurance firms and banks can use this information to reject loans or demand higher premia based on individual socio-economic information available through this data. There are other scenarios, but the key question is: Why should personal data even be allowed to be published in the public domain?

An RTI filed by this author found that the Ministry of Road Transport sought legal opinion on privacy from the Ministry of Law and Justice before they published this data online in 2012. The Law ministry gave a one-page reply saying vehicle registration data is part of the public record.

The law ministry missed an opportunity to look into the issue of privacy and ignored pointing out legitimate concerns of identity fraud. But even after the fundamental right to privacy judgement in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India [W.P. (Civil) No. 494/2012 dated August 24, 2017, this data continues to remain easily accessible.

The Vahan data is not only public but shared with police, the National Crime Records Bureau, National Investigation Agency and NATGRID, which was initially supposed to be a database that linked 20 identity databases, including vehicle licenses.

It was after NATGRID was proposed that the digitization of Vahan data began in 2010. The linking of Aadhaar to vehicle registration and driver’s license also helps ensure the NATGRID linking.

The proposed NPR plans to collect Aadhaar and driver’s license data to bolster intelligence databases. As the Ministry of Road Transport cannot link Aadhaar with driver’s license without a law—as license is not a subsidy to link Aadhaar as required by the 2018 SC judgement—the Ministry of Home Affairs is doing that job under the NPR.

(Srinivas Kodali is an independent researcher working on data, internet and governance.)