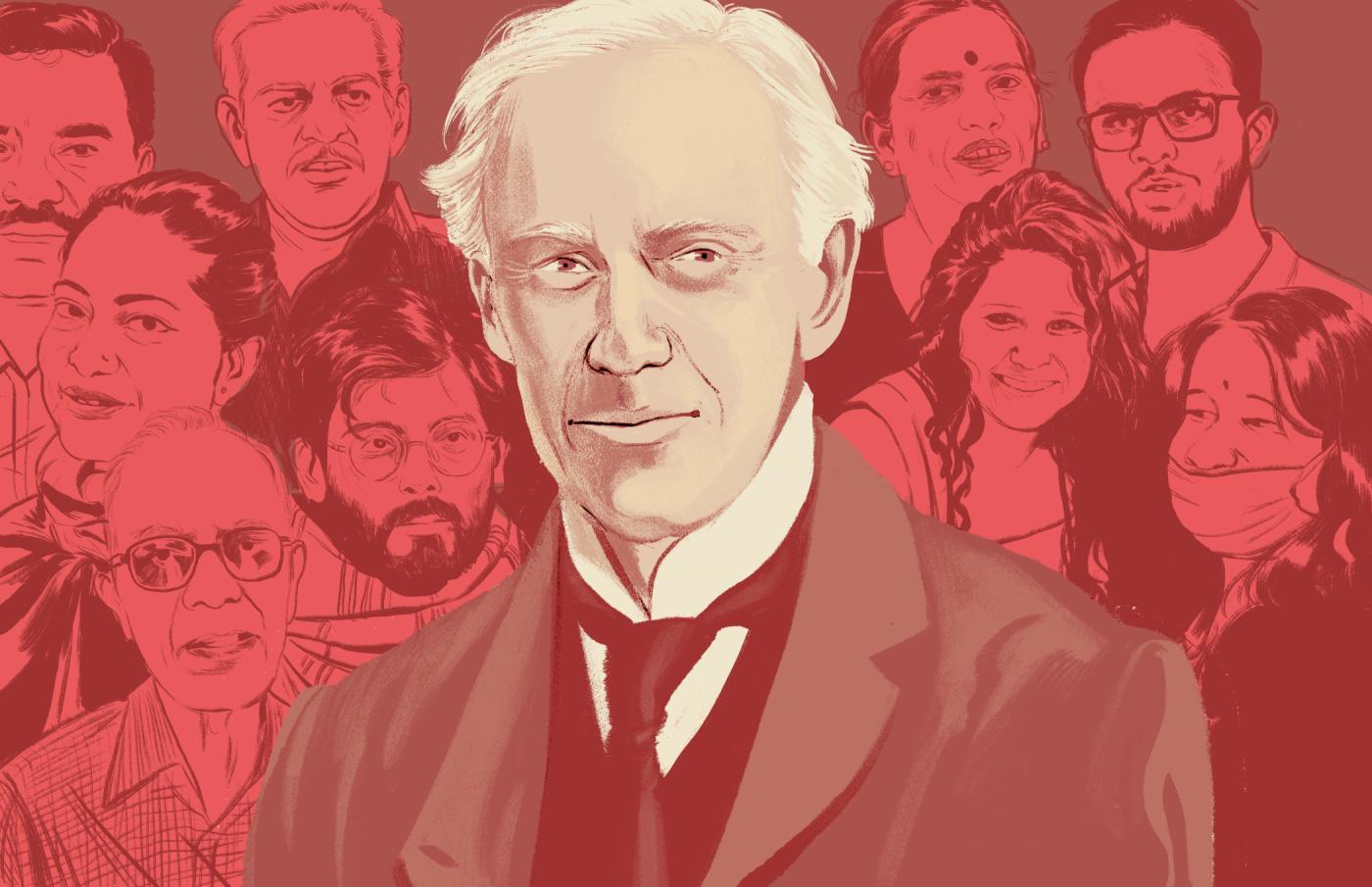

New Delhi: In 1919, the colonial government in India passed the controversial Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act. This statute authorised the colonial administration to indefinitely jail, without trial, persons it suspected of terrorism. Popular protests against this law cemented the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, and ruthless repression climaxed in the massacre of protestors in Jallianwala Bagh.

More than a century later, descendants of this much-hated law are being widely weaponised by governments in free India, both to suppress the freedom to dissent and to stigmatise and indefinitely incarcerate dissenters and protestors without trial.

These extraordinary laws abridge various rights of accused persons to fair investigation, trial and bail. Belated popular revulsion against these laws led the United Progressive Alliance government in 2004 to repeal the anti-terror Prevention of Terrorism Act. But the same government reintroduced many features of terror laws into the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967.

Unlawful activities under this law are those deemed to threaten India’s integrity and sovereignty; and terror activities those meant to threaten the security of India, or to strike terror in people. These definitions are ambiguous and blanket. This allows (as in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case) alleged Maoist beliefs and linkages to constitute crimes under UAPA.

In the case alleging an insurrectionist conspiracy behind the Delhi 2020 riots, what is being treated as a terrorist act is public opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, which protestors have called discriminatory to Indian Muslims and violative of India’s secular constitution. In effect, this statute enables the state to equate opposition to government policies and laws with treason and insurrection, restricting acceptable citizen action–in the words of law scholar Shahrukh Alam–to be “neither overtly antagonistic to the government, nor loudly wishing for political change, as well as (having) at least, a working relationship with majoritarian sentiments”.

The Evidence In UAPA Cases Does Not Matter

The UAPA makes bail extremely difficult, because if the police case diary constructs a prima facie case of terror crimes, courts are barred from granting bail.

As Gautam Bhatia (a member of the Article 14 editorial board) observed, “The case diary and the charge sheet is the version of the state. Therefore, under the UAPA, as long as the state’s version appears to make out an offence, a court cannot, under law, grant bail”.

It does not matter if the evidence presented in the case diary is riddled with obvious infirmities and is patently fake. This can be challenged only during trial. But trials can indefinitely be delayed by periodically introducing supplementary charge-sheets with new arrests. This means it may be years before a person gets the chance to prove her innocence, and all of this time is spent in jail.

We have seen in recent times large numbers of persons jailed for alleged terror crimes under other extraordinary laws for years, even decades, who are finally acquitted. But there is no public apology, no reparation, even less accountability of the police and prosecution for falsely framing these persons.

The Delhi High Court, in the Zahoor Watali case in 2018, scrutinized the police case diary for its plausibility and consistency, but the Supreme Court overruled it, indicting the High Court for conducting a “mini-trial”, reiterating that the law allows the court only to be satisfied from the evidence submitted by the prosecution that a prima facie case stands against the accused.

Again, in June 2021, the Delhi High Court ordered bail to three student activists under UAPA, once more subjecting the police case to close scrutiny–not for ascertaining the probability of guilt, but the believability of the allegations. It maintained that “offences under the UAPA are treated as extremely serious, inviting very severe punishment; and therefore, the formation of an independent judicial view by the court at every step of the way, is imperative.”

But once again, while the Supreme Court did not reverse the bail granted to the students, it stayed the effect of the order and observed that the wide examination of the evidence presented before it by the police was “something very surprising”.

Meanwhile, the police seem unembarrassed by the majoritarian partisanship of their actions (and inactions). The three students are charged with making inflammatory speeches during the protests (incidentally without actual evidence), and “misleading” Muslim audiences that the CAA discriminates against them. This means that disagreeing with the official version that the law doesn’t discriminate is unlawful and terrorist.

Police Ignore Hate Speeches Of BJP Leaders

To date, the police have refused to treat hate speeches made by senior BJP leaders, culminating in the Delhi riots, as even culpable criminal acts, let alone acts of terror.

On 19 December 2020, C T Ravi, Minister of Tourism of Karnataka ominously threatened Muslims, “If you've forgotten about what happens when the majority loses patience, just look back at what happened after Godhra. The majority here is capable of repeating it. Don't test our patience.” On 27 January 2020, union minister Anurag Thakur, after criticizing the Shaheen Bagh protest, chanted, “Desh ke gaddaron ko (traitors of the country) …”, with the crowd hitting back with “goli maaro s****n ko (shoot them all)” several times.

On 28 January 2020, BJP member of Parliament (MP) Parvesh Varma stoked hate with incendiary allegations: “The people of Delhi know that the fire that raged in Kashmir a few years ago, where the daughters and sisters of Kashmiri Pandits were raped…caught on in UP, Hyderabad, Kerala, the same fire is raging in a corner in Delhi. Lakhs of people gather there. … These people will enter your houses, rape your sisters & daughters, kill them”. On 1 February 2020, Ashok Pandey of the Hindu Mahasabha valorised Gopal Sharma, a youth who shot a Jamia student as “true nationalist like Nathuram Godse” for offering Jamia students “instant azadi”. On 2 February 2020, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath claimed (falsely) that the Delhi government fed protestors biryani, while we (the BJP) give them bullets.

The police have resisted even registering complaints in many of these cases, and certainly not found any of these to be unlawful acts of terror.

The High Court had found that in the case against Asif Iqbal Tanha there was a “complete lack of any specific, particularised, factual allegations… that would make-out the ingredients of the offences under…UAPA”.

In the Devangana Kalita case, the court concluded: “The making of inflammatory speeches, organising chakkajams, and such like actions are not uncommon when there is widespread opposition to Governmental or Parliamentary actions. Even if we assume for the sake of argument… that in the present case inflammatory speeches, chakkajams, instigation of women protesters and other actions… crossed the line of peaceful protests permissible under our Constitutional guarantee, that however would yet not amount to commission of a ‘terrorist act’ or a ‘conspiracy’ … as understood under the UAPA.”

Although its effect has been stayed by the Supreme Court, the legal and moral clarity of the Delhi High Court judgment was clear. It required the police to build credible and responsible cases under anti-terror laws; it said the police case must not blur the lines between permissible protest, criminal acts and acts of terror; and its said transgression of these lines, grievously erodes democratic freedoms.

(Harsh Mander is a human rights and peace worker, writer, columnist, researcher and teacher who works with survivors of mass violence, hunger, homeless persons and street children.)