New Delhi: If an amendment to a 54-yr-old law is passed by Parliament in its ongoing session, you will not be able to—without a birth certificate—enrol for education, get a driving licence or passport, be a voter, get married, get a government or public-sector job.

While this is one of the many proposed changes meant to improve India’s birth-and death-registration system, many studies have previously revealed how the births, and deaths, of millions of India are currently not registered.

Among these millions left out of India’s birth-and-death count, the worst off are women—a 2021 study found India has the most unregistered female deaths among 41 nations—the poorest people and states lacking health facilities.

These lacunae are evident despite more than half a century of the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969, and despite the union government’s insistence that India’s birth registration system has few flaws.

The premise for the changes that Parliament is set to discuss—the Bill was tabled on 26 July 2023—to the existing law is not in question: A good database of births and deaths is essential to India’s health and childcare systems. Policy planners must know exactly a variety of related data, including how many are born and die, at what rates, major causes of death, and children in need of adoption.

Since data must precede planning, the existing Act mandates the concerned authorities to work towards “unification” of the registration system, which is a laudable goal.

More than half a century later, India is far from reaching that goal.

Among the positive changes in the proposed new law, called The Registration of Births & Deaths (Amendment) Bill 2021, is the establishment of a special authority to register births and deaths during disasters and a national database of births and deaths.

Among the negative changes is the requirement of mandatory disclosure of Aadhaar, in violation of a Supreme Court order, of family and close relatives when someone dies and a stipulation that social welfare schemes (including education) will depend on the newly-issued birth certificates.

Many of the changes proposed by the new legislation are premised on the stand taken by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party that India’s registration system is near-foolproof, an argument most evident during a controversy over how many Indians died in the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Covid-19 Death-Count Dispute

In 2022, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that 4.7 million Indians died during the Covid-19 pandemic. Since this was roughly 10 times India’s official count, the union government contested the WHO data, calling WHO’s figures an “overestimation” stretching to “the limits of absurdity”.

A union government press release at the time defended India’s existing registration system as “extremely robust” and claimed that all deaths occurring in the country in the year 2020 were registered. Some of the fuzziness in counting deaths in India is connected to the way the authority to do so is distributed.

The Indian Constitution distributes power between the union and the states by way of three “lists” in Schedule VII—the union list contains subjects on which only the union can make laws; the state list, on which only the states can; and the concurrent list, on which both the union and the states can.

The original draft of the Constitution placed “registration of births and deaths” in the state list; it was, however, removed from that list without much discussion in the Constituent Assembly, and added to the concurrent list, where it now sits. This means that States can also register births and deaths, so long as they don’t fall foul of a Parliamentary law on the subject.

It was only in 1969 that Parliament made a law on the subject, the Registration of Births and Deaths Act. Until then, the field was covered exclusively by state laws. The need for a central law was felt presumably because each State was carrying out the task differently.

Despite the 1969 Act, the system of birth and death registration in India has been described as fragmented and lacking coordination.

A New Hierarchy Of Authorities

The Bill, as it currently stands, creates a hierarchy of authorities, from the national to the local level.

It establishes a national authority called registrar general, India (section 3), and a state-level authority called the chief registrar (section 4), a district-level authority called the district registrar (section 6), and an authority at the “local level” called the registrar (section 7). The registrar can further appoint sub-registrars for assistance in their local area (section 7).

The proposed change is this: in addition to existing authorities, the registrar may appoint a special sub-registrar for on-the-spot registration of deaths in case of a “disaster”. This provision is possibly suggested with a Covid-like situation in mind. The special sub-registrar will also be empowered to issue extracts of the register to those who require it.

A New Database To Update Other Databases

The national authority under the existing law, the registrar general, is required to coordinate with state-level chief registrars and ensure a uniform system of registration of births and deaths. In turn, the chief registrars must coordinate similarly with the smaller offices.

But what is conspicuously missing in the Act is an express provision for a coherent database, either centrally or at the state level.

Under the proposed changes, the registrar general will be mandated to “take steps to coordinate and unify the activities of Chief Registrars, in the matter of… the database of registered births and deaths”.

The use of the word “database” is new and clarifies that the intent is to enhance the quality of available information. The registrar-general is also required to maintain a database of registered births and deaths nationally.

This central database may be used for various purposes, such as to update the population register prepared under the Citizenship Act 1955, electoral registers or electoral rolls prepared under Representation of People Act 1951, Aadhaar database, ration card database, passport database, driving licence database, “and other databases at national level”.

A similar mandate is proposed for the chief registrars, who must take steps to maintain “a unified database of civil registration records at state level, and integrate [it] with the database at national level”.

Clearly, the idea is to create a central database handled by the registrar general, India, which is fed by the databases of the respective states collated by the chief registrars.

Compulsory Disclosures & Appeals

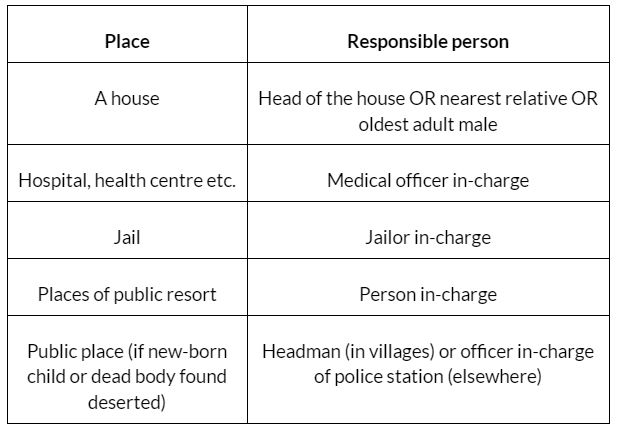

The current law compels disclosure of information about births and deaths. Depending on where the birth/death occurs, the following are mandated to disclose the fact to the registrar:

Non-disclosure is an offence punishable with a fine of up to Rs 50.

Under the proposed changes, where the death takes place in a hospital, the hospital shall issue a certificate to the registrar and the nearest relative of the deceased describing the cause of the death. The apparent idea is to create a reliable record which is contemporaneous with the event.

The proposed amendments also introduce a provision for appeal, which is useful. Should any person be aggrieved by any order of the registrar or the district registrar, an appeal can be filed against the registrar’s order before the district registrar, and against the district registrar’s order before the chief registrar. This ensures that wrong entries or the refusal to make an entry can be appealed.

The Problems Within

In addition to the information relating to the birth or death, the informant must also disclose Aadhaar numbers—in case of birth, of the parents and the informant, and in case of death, of the deceased, parents, spouse, and the informant.

The legality of this Aadhaar requirement contradicts a landmark 2017 Supreme Court judgement, popularly called the Puttaswamy case, which prohibits the violation of the fundamental right to privacy except if it is necessary to achieve a legitimate state aim.

As Justice D Y Chandrachud, now chief justice, explained in that case:

“While it intervenes to protect legitimate state interests, the state must nevertheless put into place a robust regime that ensures the fulfilment of a three-fold requirement. The first requirement that there must be a law in existence to justify an encroachment on privacy is an express requirement of Article 21. Second, the requirement of a need, in terms of a legitimate state aim… ensures that the law does not suffer from manifest arbitrariness… The third requirement ensures that the means which are adopted by the legislature are proportional to the object and needs sought to be fulfilled by the law.”

As it is presently worded, the Aadhaar requirement in the proposed new law seems overbroad and unnecessary.

Also problematic in the proposed new law is that new births registered in the database will be used to prove the date and place of birth for at least six purposes: educational admissions, issuing driving licences, voter registration, marriage registration, appointments in governmental bodies/ public-sector units and passport applications.

In its present formulation, the provision does not make it clear as to whether the database will be considered the only authentic source to ascertain a person’s birth date and place.

If yes, it might be challenging at best, and unjust at worst, for the Government to implement this provision without taking up adequate awareness campaigns. As previously mentioned, India’s registration system has serious deficiencies. It would be prudent to cure the deficiencies before embarking on an exercise that could potentially exclude persons who have no access to registration.

These problems are more glaring because a series of studies, as I previously mentioned, have established the flaws in the current system of counting deaths and births.

Still ‘Under Development’ After Decades

A 2010 paper described the birth-and-death-registration system as marred with “incompleteness”, with “poor quality of data on causes of death recording” and a “lack of proper implementation at lower geographical units”.

Due to these flaws, there is a mismatch between the data present in the health system and “what is required by the public health planner, medical scientist, epidemiologist and researcher”.

A 2016 study described India’s civil registration and vital statistics system as “still under development”, which means India is forced to rely on alternative sources to understand its population, assess the biggest health risks and evolve health programmes to address those risks. These alternative sources include census data, sample registration system, and some specific governmental data-collection projects, such as the National Family Health Survey.

The Inequality In Birth & Death Data

A 2022 study revealed striking geographical disparities in patterns of registration across India. Take, for instance, registration of deaths of women. In 251 districts (out of 707 studied), over 80% of the female deaths were registered, but in 122 other districts, the number was less than 40%.

Mumbai district in Maharashtra recorded the highest number (100%) of deaths of women, while Kurung Kumey district in Arunachal Pradesh recorded the lowest (5%). The wide disparity among districts “is due to unequal socio economic development, lack of awareness and lack of health facilities”, said the authors of the 2022 study.

Registration of male deaths showed similar disparities, though the general percentage of registered male deaths was higher than the general percentage of female deaths, which “could be attributed to a lower proportion of women employed in the formal sector and hence a perceived lower need to register female deaths”.

According to the 2022 study, no more than 48% of male deaths and 36% of female deaths were registered in India. A different study by Jayanta K Basu and Tim Adair found these statistics to be 85% and 74% respectively. Both studies agree that female deaths are registered less than male deaths.

A more global study in 2021 said that India had the most unregistered female deaths (in absolute numbers)—close to 600,000—as compared to 41 other countries that were studied. The male-female disparity was second highest in India after Myanmar and followed by Libya, Zambia and Nepal.

Besides sex, the 2022 study found a variety of factors, such as age, residence, region, education, wealth, religion, caste, and even the existence of health insurance, to be correlated with death registration. For instance, in the age groups above 25 years, registration percentages were found to fluctuate between 72% and 80%, but for children till the age of 14, they remained between 34% and 40%.

Factors that may influence the registration of child deaths were “inheritance, pension claims and insurance” and, conversely, “lack of financial benefits from the death of a child and stigma related to premature death of a child”. In urban areas, 83.3% of deaths were registered, in rural areas, 66%.

Up to 62.6% of those who were illiterate had their deaths registered while 81.7% of deaths of those with education higher than secondary school were registered. Similarly, the deaths of 87/1% of the wealthiest were registered compared to 51.7% of the poorest.

With such inequality in data, there is little doubt that the birth-and-death-registration system requires change. The new Bill, it appears, has a mixed bag of proposals in delivering that change, some that should improve conditions, others that will worsen them.

(Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj is a lawyer practising in the Supreme Court of India.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.