Dehradun, Uttarakhand: On the evening of 28 August 2025, a vehicle carrying a batch of sun-dried animal bones was set on fire right outside the Selaqui police station in Dehradun’s Vikas Nagar tehsil, located on the outskirts of Uttarakhand’s capital city.

A mob attacked the three men in the vehicle. A video of the incident went viral on social media, showing the burning vehicle with its consignment of bones—the primary raw material in bone china crockery and a range of artefacts—still inside.

Haseen Ahmed, 30, arrived at the scene shortly after the attack began, bearing original documents from a contractor licensed by the district panchayat, certifying that the vehicle had the requisite permissions to transport the bones.

Ahmed, a resident of Rampur village in Sahaspur block about 10 km away, works with his three brothers in the family’s traditional occupation—collecting carcasses from villages and bringing them to a designated site near the Sheetla river, where the carcasses are left to dry for several days until the bones can be collected.

“They didn’t even look at the papers,” he told Article 14 about the members of the mob he had tried to reason with. “They just kept beating us.”

Having received a phone call that a mob had halted his vehicle near the Khatu Shyam temple, Ahmed had rushed to the spot. By then, the driver had fled. A mob of 150 to 200 men attacked Ahmed and two other workers accompanying the vehicle. “I couldn’t even tell who was hitting us, anyone and everyone joined in.” Had the police not arrived, they could have died, he said.

Ahmed, who sustained head injuries, went to a local hospital from where he was referred to Doon medical college.

“They were Bajrang Dal people,” said Ahmed. “Over the last three-four years, they have been creating trouble for us.”

Workers like Ahmed have, for generations, collected animal carcasses, removing the hide and waiting for the skeletal remnants to dry naturally under the sun.

Once a truckload of bones is collected, over a period of three to five months, these men transport the bones to markets in Saharanpur, Hapur, and elsewhere in western Uttar Pradesh (UP), about 75 km west of Dehradun.

Traders in western UP, the key link between village-level workers like Ahmed and industrial buyers, supply the bones to large processing mills for use in various industries including fertilisers and bone china tableware.

In Dehradun district alone, about 150 people including contractors and workers are engaged in the trade of dead animals. Most contractors are scheduled caste, while the majority of the workers are Muslim.

Many are from families that have done this work—peacefully—for generations. They told Article 14 that while attacks against them and intimidation began five to six years ago, the violence intensified in 2025. Those who depend on this trade for their livelihood live in fear of attacks, workers and contractors said, and many are trying to find other means of livelihood.

Following the Selaqui incident, police registered cases against the victims and the perpetrators of the mob attack—stating that the vehicle was engaged in illegal transportation of animal bones (notwithstanding the written permission that Ahmed had), and a case of arson against the mob.

Police sub-inspector P D Bhatt of the Selaqui police station told Article 14 that the mob included Bajrang Dal members and also local residents. “The bones have been sent to Hyderabad for testing, and it is still unclear who set fire to the vehicle,” he said.

‘Where Will You Bury So Many Animals?

Weeks later, Article 14 met Irshad Ali, 48, as he and two others unloaded the carcass of a large animal from a vehicle and carried it to the dry riverbed of the Sheetla river in Sahaspur.

At the designated site for carcass disposal near Langha Road, the landscape lay bare, marked by uneven mounds of earth and scattered bones. The air was heavy with a foul smell, but Ali said they were used to it.

He and his fellow workers left the carcass under the shade of some bushes, out of sight. Vultures hovered in the sky while dogs fed nearby. A small congregation of egrets perched on a raised mound, watching quietly.

Ali said the 10-15 workers at the site planned to call for a strike. “They want us to stop removing the skins, and instead bury all the animal carcasses,” Ali said.

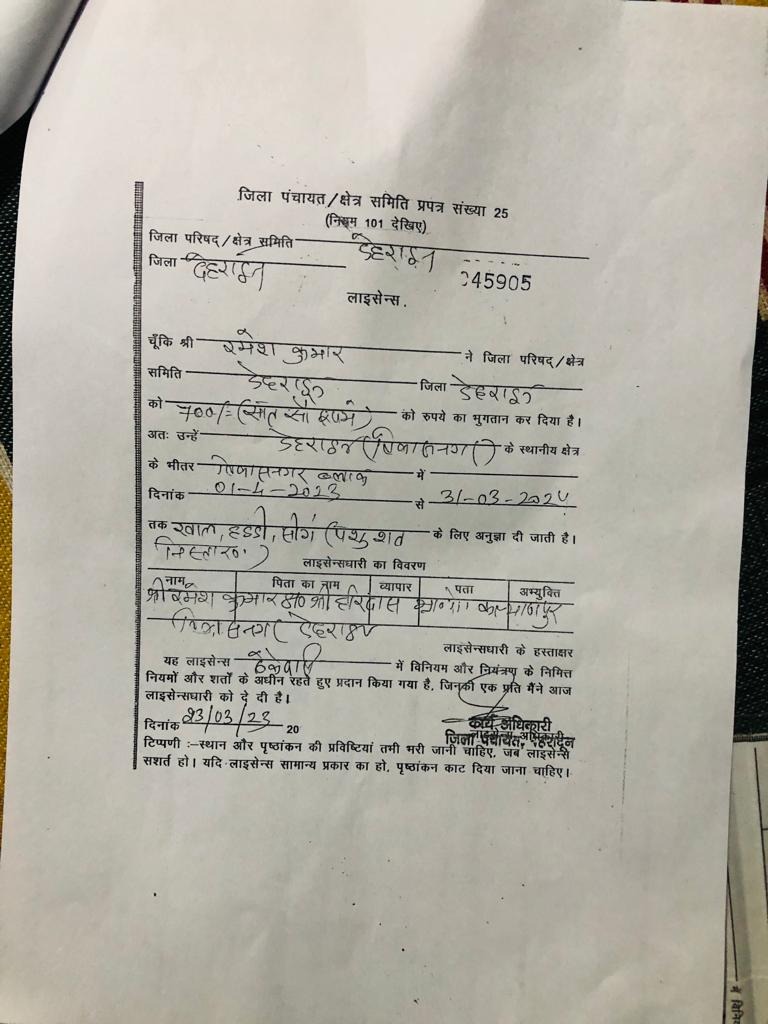

Ahmed and Ali, and the dozen or so others, collect and transport carcasses that are dried in the open area of the riverbed. They are employed by Ramesh Kumar, a contractor licensed by the district panchayat for carcass disposal and for the use of bones, skins and horns, in the Vikas Nagar area.

In Dehradun district, such licenses are issued by the district administration through cooperative bodies that are tasked with dead animal disposal, although elections to these cooperative societies have not been held for at least 10 years.

“We bring 10–12 dead animals here every day,” said Ali. “How many can you bury, and where would you find the space to bury them all? Just think how many will pile up in a month or a year.”

Kumar displayed a copy of the licence issued to him by the Dehradun district panchayat. Those who take offence at their work could easily verify from the police or other authorities whether the work was legal and licensed by the local government body, he said. “Instead, they beat our people, burned our vehicle right in front of the police station, and then filed a case against us.”

Even as workers contemplated going on strike, on 23 September, another incident broke out in Dehradun city’s Raipur area. Members of right-wing Hindu organisations clashed with a team transporting dead animals. The members of the Hindutva groups tried to damage a vehicle, leading to fresh tensions.

The Dehradun municipality also wrote to the district’s senior superintendent of police seeking action against those obstructing the work of collecting carcasses.

Satish Kumar Tripathi, additional chief officer of the Panchayat, met workers and gaushala (cow shelter) operators in the last week of November 2025. Acknowledging that there appeared to be politicisation in the name of cow protection, Tripathi told Article 14 that if the administration were to stop issuing tenders for the disposal of carcasses and instead assign the task of removing dead animals directly to workers, the cost would be around Rs 5,000 per animal.

“If 100 animals arrive in a single day, the daily cost would be Rs 5 lakh, or roughly Rs 1.5 crore per month,” he said. “Additionally, we will need land for burial of the carcasses.”

Muslims Targeted, Dalits Affected Too

The vehicle belonged to another contractor, Rajesh Kumar Barman, 55.

Angry, hurt and visibly afraid, Barman said he has no hesitation in calling himself a Dalit. For generations, his family had undertaken the removal of skin and bones from animal carcasses.

“Such incidents never occurred earlier,” he said. “What’s happening now is that in an attempt to weaken Muslims, the Dalit community is also being targeted and humiliated.” One incident triggered another, he continued, and attacks against vehicles transporting animal remains were being reported from multiple districts of Uttarakhand, and from neighbouring Uttar Pradesh. “That’s how these attacks are spreading, from Agra to Hapur, and now to Dehradun.”

Barman said security was now such a concern that his family members were uncertain about continuing in this line of work. “The social stigma was already driving many away,” he said. “Now my two brothers and four sons work as daily wage labourers instead.”

Striking Workers, Decaying Carcasses

Barman said contractors like him earn only about Rs 15,000-Rs 20,000 a month once all expenses have been covered and the workers paid.

Workers like Ali and Ahmed, who do the actual work of collecting and transporting the bodies, also earn roughly the same sum, barely enough to keep their families afloat.

On 24 September, about 50 workers went on strike, bringing all work on recovering skin, bones and horns from dead animals across Dehradun district to a halt.

By the end of the second day of the strike, complaints were pouring in at Dehradun Municipal Corporation, the district administration and the office of the town’s mayor that there was nobody available to collect carcasses. The stench of decay spread, and the situation became especially difficult for cattle owners in rural areas, including dairy operators and cow shelters, where bodies of dead animals lay unattended.

Rumi Ram Jaiswal, former gram pradhan (an elected village chief) of Chharba, had to bury his dead cow himself during the strike. He buried the animal in his field with the help of villagers, after it became evident that nobody would come forward to take the carcass.

“What about those who don’t have land and barely manage two or three animals?” he said. “This politics is ruining our way of life.”

State BJP leader Ravindra Jugran said the issue should not be politicised.

“People who have been doing this work for generations earn their livelihood from it, and this work is also essential for maintaining a clean environment,” said Jugran. Those holding a licence from local authorities are conducting government work, he said, and those setting fire to their vehicles should be seen as obstructing official work.

“It is now the police’s responsibility to identify and take action against these people,”said Jugran, without naming the Bajrang Dal or other organisations.

Communist Party Of India (Marxist-Leninist) state secretary and political activist Indresh Maikhuri, reacting to the incident, said Hindutva organisations were seeking to “communalise everything”.

“None of those who call themselves cow protectors actually raise cows,” said Maikhuri. “They create an environment of violence in the name of cows.”

If dead animals were left unattended, villages, towns and any other settlement would struggle, said Maikhuri.

“Most people cannot do this work; the community that carries it out deserves recognition and respect,” said Maikhuri. “Instead of acknowledging their role, society is criminalising them.”

Legal Gap

The charges filed against the people whose vehicles were set on fire in Selaqui were for illegal transportation, even though their official slips specifically mentioned the use of bones, horns and skins from carcasses.

The Uttarakhand Protection of Cow Progeny Act, 2007 and its Rules notified in 2011 provide no clear guidance on this issue, said experts.

Dehradun Superintendent of Police (Rural) Renu Lohani said the problem arose from the fact that while municipalities or district panchayats issue tenders and grant permission for disposal of animal remains, the law is silent on the issue of their transportation.

“The Act does not explicitly say that they can be transported, nor that they cannot. Once the remains are collected, they have to be disposed of somewhere,” said Lohani. “If the district panchayat allows the use of bones, horns and skins, they must be transported to be put to use.”

Barman, the contractor, added that when the Uttarakhand government enacted the law in 2007, they only mentioned the ‘disposal’ of the carcass. “There is no specific reference to burial, nor any mention of the use of skin, bones, and horns. The law needs to be amended,” he said.

The Uttarakhand Protection of Cow Progeny Act, 2007, was adapted from the Uttar Pradesh Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 1955. In 2022, the Allahabad high court observed that the transportation of cow skins or leather does not violate the UP Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act.

Administrative Hurdles

In 2025, Panchayat elections in rural areas created disruptions in the usual permission process for the work of handling animal carcasses. The community typically receives authorisation to handle animal remains from 1 April to 31 March, which was extended for an additional three months in April 2025.

By July, during the election period, workers and contractors technically did not have permissions as the extension had run out, but they continued their work in order to manage dead animals’ remains.

Tensions escalated when the strike led to public resentment, as decaying animal remains began to cause problems.

Residents approached the police and the district panchayat, prompting a meeting between the newly elected panchayat members, district administration, and police. Following this, permissions were extended until 31 October, with the condition that workers must inform the police before transporting carcasses.

The district panchayat remained uncertain about the next course of action, while newly elected chairperson Sukhwinder Kaur sought directions from the government.

“We know this traditional work has been carried out for centuries and continues in other blocks of the district,” said Kaur. “But in Vikas Nagar and Sahaspur areas, due to protests from some people, we have not been able to find a solution.”

Kaur said she would write to the government to decide what to do.

Dehradun Struggles To Manage Dead Animals

The disposal of animal carcasses remains a major challenge across urban and rural areas of Dehradun district, as well as in the rest of the state, particularly in the absence of any officially designated site or crematorium for dead animals.

Deputy director of the Uttarakhand Animal Welfare Board, Urvashi, who uses only a first name, expressed her frustration at being unable to identify suitable land for disposal of animal carcasses. “We have tried several locations, but local residents raise objections due to the foul smell,” she said.

Between 2020 and 2025, she said, the state administration had more than once allocated budgets and drafted plans for a facility to dispose of carcasses. “... whenever we identify land, we have to abandon it because of public opposition.”

In fact, animal remains and their disposal sites play a crucial role in sustaining raptor birds’ food cycle. The Sheetla riverbed in Vikas Nagar, where Ali and his colleagues work, is one such site.

Wildlife expert Sunny Joshi of international non-profit Worldwide Fund For Nature (WWF)-India explained that the Sheetla riverbed serves as a feeding ground for vultures, with 24 species of raptors documented as visiting.

“This includes eight raptor species listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) ‘red list’ of threatened species, among them the Himalayan vulture, Egyptian vulture, and steppe eagles,” he said.

Established in 1964, this evolving red list has emerged as a comprehensive source of information on global extinction risk status of various species.

While the big birds feed on animal carcasses in sites such as Sheetla, the smaller insect-eating birds and butterflies thrive on the nutrient-rich soils left behind. “It’s a natural cycle in balance,” Joshi said.

As Ali looked across the Sheetla riverbed, the land his father and grandfather once tended, Haseen Ahmed said, “This is how we earn our livelihood. If not us, who will handle these animals?”

He said this was not work an “ordinary person” could do, and those engaged in the profession learnt the skill from their fathers. “Now we are in fear,” said Ali. “We are doing legal work, but we have no protection.”

(Varsha Singh is an independent journalist who writes on environment, health and public policy.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.