Purulia, West Bengal: Dressed in a colourful cotton saree, Fulan Dori watched as about 200 people walked through her village in the Ajodhya Hills in West Bengal’s Purulia district in early April this year.

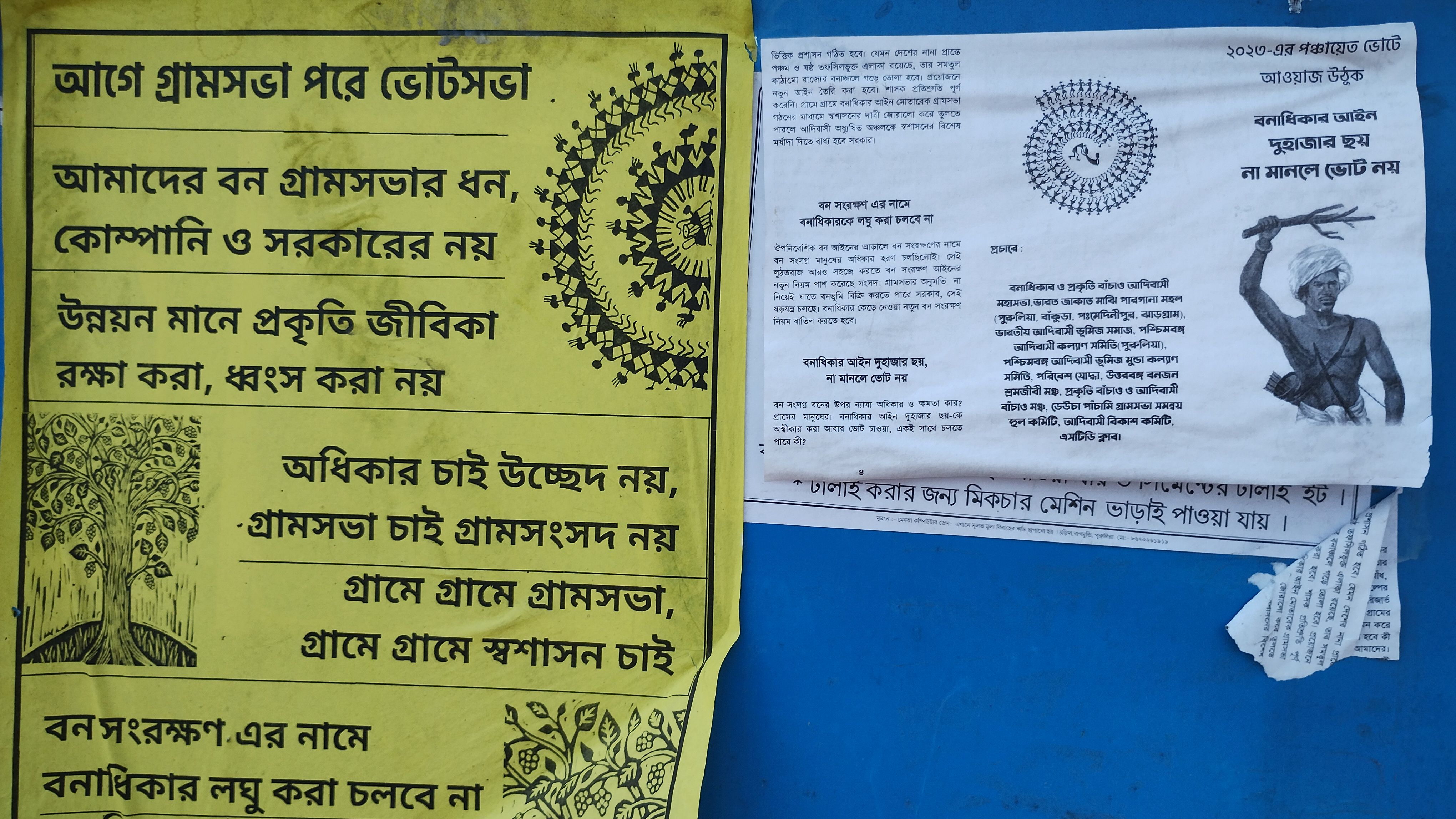

“Na Bidhan Sabha, na Lok Sabha. Sob cheye boro gram sabha (neither Vidhan Sabha, nor Lok Sabha, the most important is gram sabha),” shouted the line of protestors, mostly school teachers, farmers, farm labourers and activists of the Prakriti Banchao O Adibasi Banchao Mancha, or Forum to Save Nature and Tribals.

Men covered their heads with a gamchha (towel), and many women were dressed in the panchi saree, traditional attire of women of the Santhal, a word that means peaceful man

“What is this about?” asked Dori, 25, as the crowd sloganeered and distributed leaflets among Adivasis and forest dwellers of the Ajodhya Hills, part of the forested Chota Nagpur plateau along the borders of West Bengal and Jharkhand.

“We must have gram sabha in every village. It is our right under the Forest Rights Act of 2006,” someone from the crowd shouted, referring to the general body of a village council.

The Ajodhya Hills are a site coveted by the West Bengal government since the 1980s for four hydroelectric projects. These require a powerhouse and two reservoirs at different altitudes, using water plunging off the plateau.

In 2017, the state identified 234 hectares of forest lands and 58 hectares of “non-forest land/private land” for the proposed 12.66-sq-km catchment area of the Turga Pumped Storage Project (TPSP), one of the four. Land acquisition has started, the West Bengal State Electricity Distribution Company Limited, a state agency, in charge.

The area is home to approximately 11,000 Adivasis, mainly of the Santhal tribe, and the forests on which they depend. Large tracts of these forests will be submerged by reservoirs of the TPSP, cutting off forest-dwelling communities from their basic subsistence.

Adivasi communities accuse the West Bengal government of sidestepping consultative processes required by the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, better known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA), while acquiring forest land for the project, calling into question the legality of the acquisition.

The project’s trajectory, our investigations reveal, echoes statewide practices that violate rights and processes under the FRA and similar violations nationwide, documented extensively by independent reports (here, here and here) and media reporting (here, here and here)

The Lure Of The Ajodhya Hills

A pumped storage plant is a hydroelectric energy storage facility that has two reservoirs at different elevations, pumping water from the lower to the upper reservoir. When demand rises, water is released from the upper reservoir to power turbines to generate electricity.

The Ajodhya Hills, dotted with streams that flow downhill, some of which become tributaries of major rivers in the region, provide the ideal topography for such power generation.

The first, among the four projects in Ajodhya Hills, the 900 MW Purulia Pumped Storage Project (PPSP) on Bamni river, was launched in 2008. The government has almost finished acquiring land for the second, the 1000 MW TPSP on Turga river—a tributary of the Subarnarekha river—and has invited tenders for the third, 900 MW Bandu Pumped Storage Project. The site of the fourth project is still being determined.

The union government gives clearance to states, in two stages, for projects related to forests—stage-I is called “in principle” approval and stage-II is the final approval. In 2018, the union ministries of tribal affairs (MoTA), and of environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC), decided that state governments must give proof of having “initiated the FRA clearance process” at the time of seeking stage-I clearance.

The union government approved the TPSP in October 2022, even as local communities continued to dispute the state’s adherence to FRA processes. Under the Centre’s Forest Conservation Rules, notified in June 2022, the state government is now effectively on its own to comply with these processes.

Consent Diluted

The FRA seeks to reverse the treatment, perpetuated since the colonial era (here and here), of Adivasi and forest-dwelling communities as ‘encroachers’ on forest land.

Community forest rights recognise traditional rights, and the right of local communities to protect, conserve or manage any community forest resource for sustainable use.

In recognising the rights of tribal and non-tribal forest dwellers over forests, the FRA directs state authorities to acquire the “free consent” of each gram sabha, a village assembly of all adult residents of the village “with full and unrestricted participation”, before handing over any traditional forest land for industrial projects.

“The Forest Rights Act was framed to restore the rights of tribals that were taken away from them during the colonial era, ‘to undo the historical injustice’ as the Act says,’” said Samim Ahammed, a Calcutta High Court advocate who deals with cases relating to environment and forest laws in West Bengal.

The gram sabha was given the role of obtaining consent so that land claims made by those who depended on forests could be considered and settled with their participation. It was also meant to ensure that projects seeking permission to “divert” forest land—a euphemism for cutting down forests—for non-forest use, such as mining, construction and other “development” projects, complied with the FRA, Ahammed explained.

Under the 2007 Rules of the FRA, which came into effect in 2008, each gram sabha must elect a forest rights committee (FRC) of 10-15 individuals, from among its members, of which two-thirds are to be from scheduled tribes and a third women.

When claims of forest rights are decided, gram sabhas must ensure that at least half the claimants of forest rights (forest dwelling scheduled tribes or other traditional forest dwellers) are present at the time of voting. Resolutions on such claims can be passed by a simple majority of all present and voting. This must precede diversion of forest land or any other development activity in forest areas.

In a 2013 judgement, popularly known as the Vedanta order, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the importance of consent from tribal communities and forest-dwellers through gram sabhas before any land was taken away.

The Supreme Court order stopped a plan by Vedanta Resources Plc, a mining company, to mine bauxite in the Niyamgiri hills of Orissa, after 12 gram sabhas rejected their mining project.

But as Article 14 reported in September 2022, the union government amended the Forest Conservation Act 1980 and diluted clauses of the FRA, particularly the requirement of consent from gram sabhas before getting the final approval, to speed up handover of forest land to project developers.

The dilution of these laws, experts said, was to allow forests to be transferred to industries without getting the consent of tribal communities and forest dwellers under the FRA.

FRA Ignored In Purulia

The legally mandated consultation process has been whitewashed in Purulia, alleged locals and activists.

“There was no gram sabha meeting,” said Sourav Prakritibadi, an environmental activist. “Villagers were not informed properly about anything related to the TPSP. One day, the government just announced the project and said gram sabhas had given consent.”

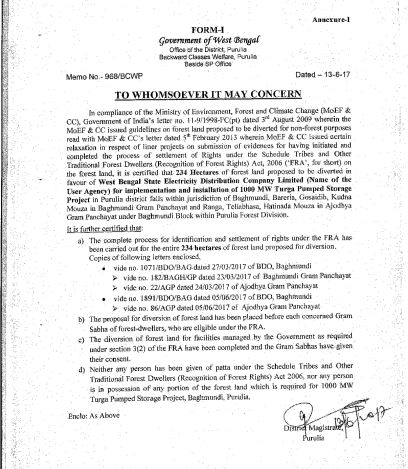

In its 2017 letter “confirming the completion of the process of settlement of Rights” under FRA 2006, the Purulia district administration “certified” that the said 234 hectares of forest land fell within the jurisdiction of Baghmundi, Barriya, Gosaidih and Kudna mouza in Baghmundi Gram Panchayat and Ranga, Teliabhasa and Hatinada mouza in Ajodhya Gram Panchayat in Baghmundi CD Block.

In West Bengal, a mouza is an administrative unit of multiple villages or settlements or habitations. There are at least 20 villages in the seven mouzas mentioned in the official letter, with an adult population of around 3,000, said Dhiren Chanre, 35, of Baruwajora village in Barriya mouza.

However, the district administration submitted only 34 signatures from two gram sabha meetings—24 from the Ajodhya gram panchayat’s gram sabha and 10 from Baghmundi gram panchayat’s gram sabha— in the letter claiming “gram sabhas have given their consent” to divert 234 hectares of forest land “under section 3(2) of the FRA”.

Fears Of Losing Livelihood

Barriya mouza is among the seven from where forest land would be diverted for TPSP. Dhiren, who was a supervisor in a Bengaluru garment-manufacturing plant, said he could not survive in a “noisy and polluted environment.”

“Adivasis need the openness and greenery of the real jungle, not the jungle of concrete buildings,” said Dhiren. His homecoming, though, has not been what he expected.

At his village in the Ajodhya Hills, Dhiren has a family of seven. They depend on a forest that would be submerged if the hydro project comes up.

“We collect dry leaves and wood to use as fuel,” he said. “Most of us also require the forest land for livestock grazing.”

The forest-dwelling communities of Ajodhya Hills sustain their livelihoods by selling Mahua flowers, honey and other products from the forest. The forest also yields medicinal plants and bamboo, wood and other resources to build homes.

Dhiren said local communities feared losing their sources of livelihood with the “felling of over 3 lakh trees [official figure is 6,816 trees] for the Turga project”.

“It (the Turga project) will destroy the forest which houses Marang Buru (literally, the great mountain or supreme deity), the sanctum sanctorum of Santhals in Ajodhya Hills region,” said Dhiren.

Divergent Judicial Opinions

In 2018, Adivasi communities filed a writ petition in 2018 at the Calcutta High Court challenging the grant of stage-I clearance by the MoEFCC to the TPSP project.

A single-judge bench in July 2019 found that the West Bengal government had not taken consent of all the affected gram sabhas, violating the FRA 2006. The court’s order states that neither of the resolutions of two gram sabhas, brought on record, “satisfies the tests laid down under the Act of 2006”.

“It is astonishing that, the Central Government approved the project 'in-principle' without being satisfied as to whether the requisite formalities under the Act of 2006 have been complied with or not,” the court said, quashing the ‘in-principal’ approval and directing the West Bengal government to act in accordance with the FRA 2006.

In its order, the court specifically defined what should be constituted as a gram sabha under the FRA.

In 2021, a division bench of the Calcutta High Court overturned the single-bench verdict and reinstated ‘in-principle’ approval. The court did not agree “that the consultative mechanism involving Gram Sabhas under the 2006 Act read with its 2008 Rules has been absolutely subverted”.

The bench did note that whether the West Bengal government’s declaration of the consent of Ayodhya and Bagmundi gram panchayats for the Turga project fulfilled the FRA “requires to be tested”.

At the same time, it acknowledged "the merits of the nature of the consultative exercise" undertaken by the state government, which followed the West Bengal Panchayat Act, 1973.

The court said “in the context of the State of West Bengal the statutory administrative unit for every Gram shall be the Gram Panchayat elected on the basis of adult franchise including women”.

Advocate Ahammed said the division bench’s order did not take into account that the use of the 1973 panchayat law, seeking consent through gram sansads, was “illegal”. He argued that “only” the FRA is applicable in “matters relating to diversion of forest lands for any kind of project”.

“The West Bengal government’s decision to hold gram sansad meetings as per the state’s panchayat act to acquire consent of forest dwellers was completely illegal,” said Ahammed. “As a result, every action of the state government from that point onwards should stand as null and void.”

Using The Panchayat Act To Circumvent The FRA

The West Bengal state government is taking a questionable legal route to justify not abiding by the processes under the FRA, in matters of acquisition of forest lands, said experts. This involves the state’s Panchayat Act, which lays the framework for the panchayati raj system in West Bengal.

Following the enactment of the Rules of the FRA in 2008, the-then West Bengal government issued an order replacing “Gram Sabha” with the Panchayat Act’s “Gram Sansad”, wrote Sourish Jha, associate professor, political science, Rabindra Bharati University, in a 2010 paper.

The 1973 West Bengal Panchayat Act defines gram sansad as an administrative body comprising individuals registered at any time in the electoral rolls of a constituency of a gram panchayat.

As we said, a gram sabha is a village assembly comprising all adult members of an individual village or habitation, with unrestricted participation of women. It is the most decentralised unit of local governance, a significant factor in the role it is given under the FRA. The Panchayat Act's gram sansad is made up of voters from multiple villages.

“The gram sansad, as part of the panchayati raj system, can be influenced by electoral politics and partisan interests,” said Jha. “Many of their decisions, including relating to forests, are dictated by the state."

A senior state government official posted in Purulia district, who did not wish to be named, called the three-tier panchayati raj system in West Bengal “the best in India made possible due to the 1973 Panchayat Act”.

“Our panchayat system already ensures that governance reaches the last person. There are many remote villages in Ajodhya Hills that have a population of less than 100,” said the officer. “From an administrator’s point of view, it is impossible to visit those villages and hold meetings for every small issue related to the forest.”

Even in matters related to forests, the officer revealed the practice of convening gram sansad and gram panchayat meetings where residents of several villages come together. He said people of any individual village “can always have a meeting among themselves” and decide if they want to bring up issues in the next gram sansad or gram panchayat meeting.

His explanation did not address the fact that the legal role of gram sabhas, under the FRA, is entirely extinguished when it comes to matters relating to forest land and rights.

In the case of the Turga Pumped Storage Project, it is unclear if the West Bengal government held gram sabha meetings even at gram sansad levels, as the letter it submitted carried 34 consent signatures taken at two meetings held at the gram panchayat level.

There are shortcuts in the state’s Panchayat Act that may be handy for authorities to undercut participatory decision-making.

Under the Act, a third of members, with a minimum of at least three members, can form a quorum for a meeting of the gram panchayat.

If a quorum is not reached, another meeting can be called within 15 days where no quorum shall be necessary to pass resolutions.

It appears evident that legal processes for diversion or acquisition of forest lands, under the FRA, are not being followed in West Bengal.

Purulia division forest officer (DFO) Karthikeyan M confirmed that for Turga and for the upcoming pumped storage projects the government would follow the Panchayat Act and hold meetings. “Here, gram sabha means gram sansad,” he said emphatically.

“The state government will have to conduct gram sabha meetings as per the guidelines laid by the FRA 2006,” said Ahammed the lawyer. “If they don’t, diversion of forest lands for the Turga project would be deemed as illegal.”

“By saying gram sabhas won’t be held as per FRA, the state is rejecting the central act,” said Ahammed. “It doesn’t have the power to do so. It cannot take away rights of forest-dwellers guaranteed to them by the Indian Constitution.”

Centre-State Tussle

In earlier years, the union ministry of tribal affairs has gently flagged West Bengal’s noncompliance of FRA processes.

In a 2013 regional consultation meeting on the FRA by the tribal affairs ministry, attended by West Bengal and 12 other states, the ministry noticed that West Bengal held gram sabha meetings at the gram panchayat level. It reminded the state that according to the FRA regime, gram sabha meetings are to be held at each village.

In response, the government of West Bengal official referred to a notification from a “few years ago” that he claimed allowed the state to operate gram sabhas as per the 1973 Panchayat Act.

When Article 14 asked Purulia DFO Karthikeyan M about this, he said he was unaware of any such notification or letter by the tribal affairs ministry.

It emerges that in a 2015 notification, the union ministry allowed the state to operate gram sabhas as ‘mouzas’ as under the 1973 Panchayat Act, but applied only to Darjeeling district.

“The 2015 notification was issued only for Darjeeling because the panchayat system doesn’t exist in the hilly regions of the district,” explained Ahammed, the lawyer. “Since the last panchayat polls were held there in 2000, FRA mandated gram sabhas could not be recognised by the local panchayat.”

Article 14 sought comment from the secretary, additional secretary and joint secretary of the union ministry of tribal affairs over phone calls and emails, seeking confirmation about the West Bengal government official's claim. There was no response. We will update this story if they do.

In February 2013, the ministry flagged several major issues with the state government's 'Action Plan' for implementing the FRA 2006, in a letter to West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee. It criticised West Bengal's decision to form FRCs at the gram sansad level, in contravention of the FRA.

Communities Cut Off From Forest Resources

Residents of Teliabhasa, one of the seven mouzas from where forest land would be diverted for the Turga project, are already in ferment.

Maloti Hembram, 27, of Teliabhasa in Ajodhya Hills alleged that ever since the land was demarcated for the project, the forest department was restricting community access to forest resources.

“I need wood to build my house,” said Maloti, struggling with a child in her arms “But the last time I tried to get some, a forest guard caught me and threatened to put me in jail. We can’t even get enough mahua flowers and honey to sell in the market now. Authorities say they watch us on camera.”

No longer able to depend on the forest for subsistence, Maloti now works as a daily-wage construction worker.

Her neighbour Dulali Hansda, a mother of two, joined in, “We manage to get the minimal resources we need to use for cooking and to generate heat during the winter. But that’s it. I work as a labourer on construction sites now.”

Both Dulali and Maloti’s husbands, who used to rely on forest produce, have switched to working on construction sites.

Purulia division forest officer (DFO) Karthikeyan M dismissed these claims. “This is far from the reality,” he said. “No one stops forest dwellers from using forest resources. They always collect mahua flowers, dry leaves, wood and other minor forest produce.”

The forest which once sustained Maloti’s and Dulali’s families would be submerged by the upper reservoir of the TPSP. They are strongly against the project, but have accepted their fate, they said.

Further Dilution Of Forest Rights

Under the FRA, as we said, each gram sabha is to constitute a forest rights committee within itself.

However, West Bengal sets up forest rights committees at the gram sansad level, not at the gram sabha. Members are selected by an external body— gram unnayan samities (village welfare committees)—and not elected from among gram sabha members, as the FRA requires. There is no requirement for the participation of scheduled tribes and forest-dwelling communities at the gram sansad level.

The state also has established joint forest management committees (JFMCs), with members chosen by divisional forest officers and made JFMCs, instead of FRCs, responsible for protection and management of forest resources, another FRA violation.

Jha pointed out that “partisan interests” influence the FRCs, and due to the functioning of the JFMCs in West Bengal, the FRCs role and importance have been “degraded”.

“The panchayati raj system and the forest department keep the power over forest land and resources within themselves, diluting the FRA’s objective to empower the forest dwellers to protect and manage forests,” said Jha

The state's poor record in distributing titles to forest-dwellers against individual and community forest rights claims, is another indication of the stifling of rights under the FRA.

The number of claims filed at the gram sabhas has remained the same since January 2017, revealing that FRCs are not working effectively. As per monthly progress reports published by the tribal affairs ministry on implementation of FRA, only 610 more claims were recommended to the sub-divisional level committees between January 2017 and November 2022, and the number of titles distributed decreased from 45,201 to 45,130 by December 2022.

‘Gram Sabha Is Our Right’

The formation of FRCs at the gram sansad level, and the influence of politically associated JFMCs, have forced local Adivasis, like Maloti and Dulali’s families, to give up their forest-based livelihoods.

Forest-dwellers in at least 15 villages have formed gram sabhas to protect their rights under the FRA as two more hydro projects are proposed to come up in the region, said Dhiren.

Prakriti Banchao O Adibasi Banchao Mancha or Forum to Save Nature and Tribals is an organised group of adivasis, school teachers and social activists, fighting for the implementation of the FRA. The forum wants gram sabhas in every village of Ajodhya Hills. It urges forest-dwelling communities to boycott the upcoming panchayat polls in the state if the demand is not met.

The West Bengal government is not taking this pushback lightly. It has challenged the ‘legality’ of gram sabhas that communities are forming.

While it may seem a David and Goliath-esque struggle, the forum’s resistance has only grown stronger.

At the rally in April this year, forum members had a singular message: “We don’t belong to any party. We want the Forest Rights Act. Without the voice of common villagers we cannot have gram sabha in every village. Remember, gram sabha is our right.”

(Niladry Sarkar is an independent journalist based from West Bengal.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.