Updated: Jan 15

New Delhi: More than a year since the final list of Assam’s National Register of Citizens came out on 31 August 2019, the government has not formally notified the NRC or issued rejection orders and reasons.

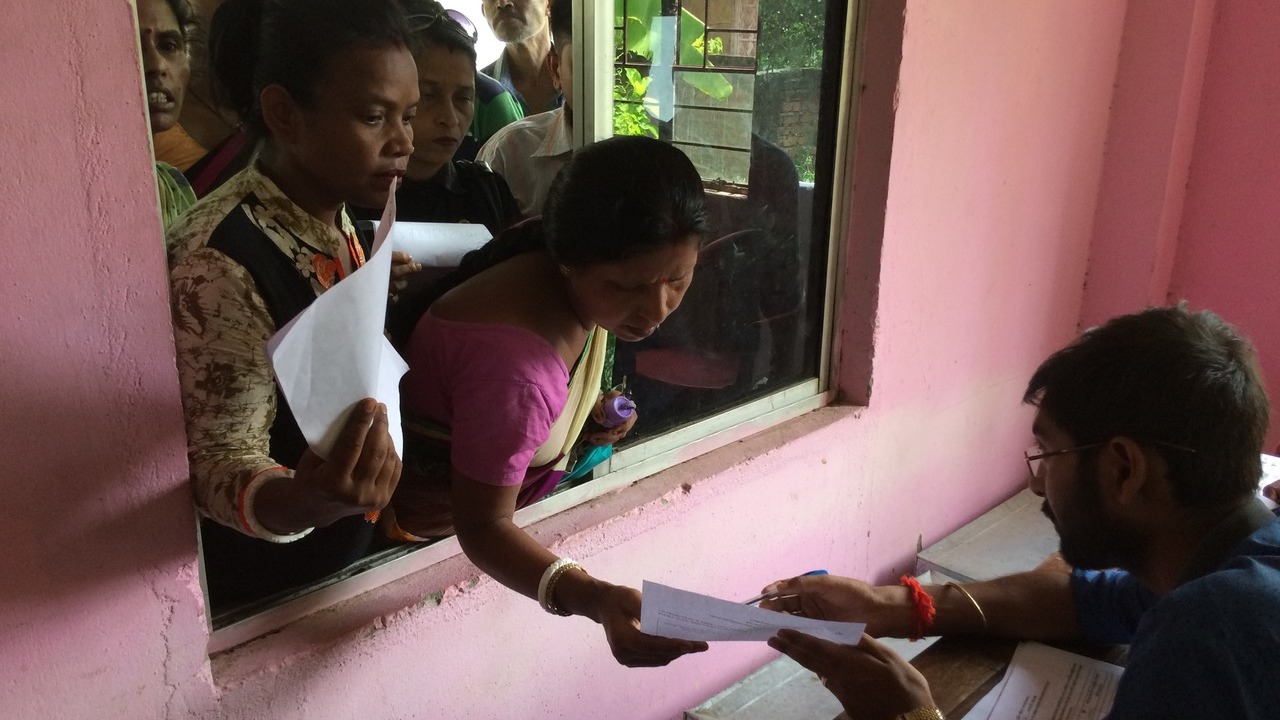

This has meant an excruciating wait for 1,906,657 excluded persons and their families, who without the orders cannot file appeals against their exclusion.

It is not only the uncertainty of the NRC’s timelines, but also of its consequences. The government has been nonchalant–even negligent–about revealing its plans for those who may fail to prove their citizenship during the appeals process.

The Costs For Human Rights

The government defends the NRC as a mechanism for identifying Bangladeshis, but at the diplomatic level, it maintains that the NRC is a purely internal matter.

Had it not been for successive court orders, thousands would still be under detention after being declared foreigners by the tribunals. The government continues to operate these detention centres basically in a legal vacuum.

This only confirms that millions of people are staring at serious human rights violations. They may be rendered stateless and potentially at the risk of indefinite detention.

This has caused considerable disquiet in India and abroad. In May 2019, senior United Nations experts working on key human rights areas expressed concern over the human rights implications of the NRC process. In August 2019, Genocide Watch expressed alarm at the ethnically-driven deprivation of nationality for millions and the risk of imprisonment. Disregarding this criticism, the Indian state has failed to take into account its national and international legal obligations.

The Right to Nationality

The Centre for Public Interest Law at the Jindal Global Law School recently released the report Securing Citizenship, which extensively maps these legal obligations. Central to these is Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which guarantees all persons the right to nationality and the right not to be arbitrarily deprived of their nationality.

India is party to numerous international conventions–on civil and political rights, racial discrimination, the rights of the child among others–that reiterate this right to nationality. It has become a part of customary international law binding on all countries including India.

There is some debate about the implications of the right to nationality. As we argue in the report, the right is best interpreted on the basis of a 1955 International Court of Justice decision, according to which a person with a “genuine link” to a country should be deemed to be its national. The test of genuine link includes birth, residence, family ties and participation in public life of a person in a country.

Article 12 of the legally binding International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) supplements this test, by guaranteeing that no one can be deprived of the right to enter “his own country”. This phrase indicates the country of the person’s long-term residence, family relations and intention to remain, along with the absence of similar ties to another country, even if the country does not formally recognize him as its national.

There is little doubt that persons excluded from the NRC satisfy both these tests. The NRC excluded people despite being born in India. The excluded persons reside and have family ties in the country often going back to generations. Moreover, they do not have such connection with any other country, let alone Bangladesh. The excluded persons consequently qualify as Indian nationals under international law.

Right Against Arbitrary Deprivation of Nationality

Consequently, those excluded also have the right under Article 15 of UDHR to not be arbitrarily deprived of their nationality. A country cannot take away someone’s citizenship without legally mandated safeguards. The processes must be provided under law. They must have a legitimate purpose, and be proportionate and necessary. Finally, they must not be discriminatory and follow due process of law.

The biggest concern about the NRC is that it placed unduly demanding–and thus disproportionate–documentary requirements on Assam’s residents to prove their citizenship. Some policies were discriminatory on the face of it. For instance, the NRC administration relaxed evidentiary rules only for what it called “original inhabitants”–a category that in practice excluded Bengalis.

What makes the existing NRC policy patently contrary to international law is the imminent consequence of statelessness. Rendering a person stateless is one of the most severe violations of human rights because it restricts institutional access to practically all other rights. Numerous international courts and conventions have recognised that all countries are under an obligation under international law to prevent and reduce statelessness.

Without a viable mitigating policy, the NRC would have disproportionate effects and be arbitrary under the law. The report recommends that if India wishes to comply with international law, the only meaningful response would be to affirm the Indian citizenship of those who are ultimately excluded from the NRC.

Right Against Arbitrary Detention

The Indian state’s cavalier attitude towards human rights is perhaps best reflected in its detention of persons declared to be foreigners.

Binding international norms like ICCPR prohibit arbitrary detention as a matter of right. Detention must have a legitimate purpose and be proportional in each case. Proportionality under international law and Indian Supreme Court’s judgments requires that detention must have a connection with its purpose, and be necessary. It follows that detention must be the measure of last resort along with regular review of individual cases.

India’s detention practices fail each of these standards. The government maintains detention centres within jail compounds, without any semblance of a transparent detention policy. It has neither clearly laid down the purpose of detention, nor explored alternatives to detention. There is no individualised review policy in place.

Even if we assume that detention is for deportation, detention practices do not meet this ostensible purpose. There is no time limit to deport detainees. In fact the government has told Bangladesh that it does not seek to deport anyone. Detention, for all practical purposes, is indefinite. This means that detention lacks purpose and is disproportional.

The Supreme Court in April 2020 directed the conditional release of the detainees who had served more than two years in detention. But regrettably, it did not test detention policies on the anvil of legality. It did not ask the government to justify why detaining thousands–all of whom are part of communities in Assam–was necessary for any public purpose, or why less intrusive mechanisms could not be evolved. On the contrary, by directing conditional release, the Court approached detention as the first rather than the last resort.

Unending Wait

Rather than addressing these severe implications of the NRC, political players have unfortunately turned it into a political football.

The Supreme Court, after having driven the process, appears to have withdrawn from the scene without displaying responsibility for the consequences of its decisions. After defending the NRC for years, Assam’s ruling party and many influential Assamese organisations are trying tooth and nail to undermine its credibility, and demanding more exclusion.

If we do not carefully consider the consequences of the NRC in the light of the law, we may be staring at a mass eclipse of rights for millions.

(Mohsin Alam Bhat and Aashish Yadav teach at the Jindal Global Law School and are at its Centre for Public Interest Law. Bhat is also on the editorial board of Article 14.)