Delhi: How many came?

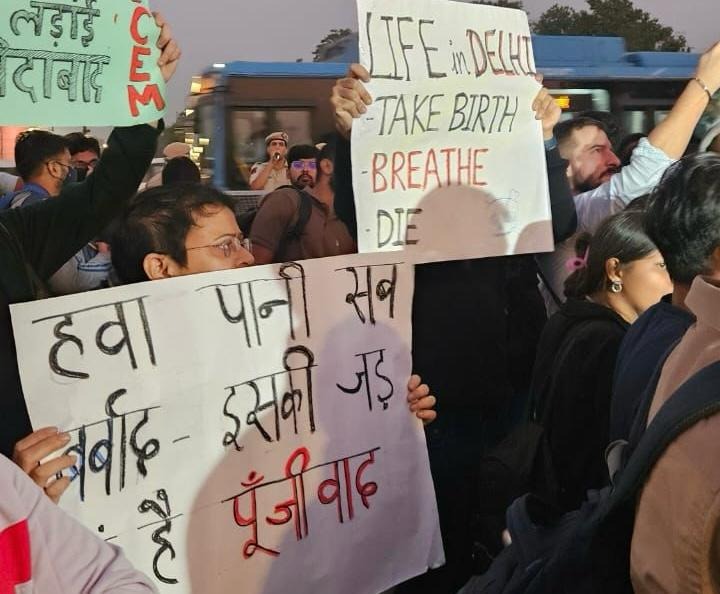

The question was about the turnout at three recent protests over Delhi’s choking air pollution—demonstrations held in a city that, every winter, disappears under a haze of smoke and dust and ranks among the world's most polluted.

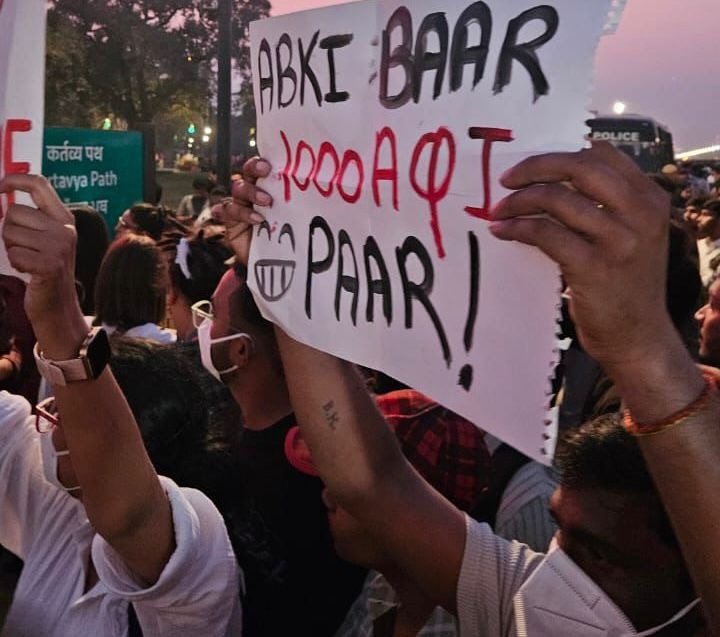

When the numbers were tallied, there were about 500 people at the first protest at India Gate, around 70 at the second at Jantar Mantar, and roughly 200 at the third, also at Jantar Mantar. So, in total, fewer than 1,000 people showed up in a city of 22 million.

The question was put to one of the most vocal campaigners behind the three protests, journalist Saurav Das, who had been championing what felt like a rare public demonstration against air pollution, even though successive governments have done little to address it.

I asked Das (who has written for Article 14) whether this could really be considered a good start, especially when turnout was so low for an issue that should cut across party lines and bring tens of thousands into the streets. Das, however, was firm: it was a good beginning.

As we went over all the reasons people didn’t show up—fear, apathy, and everything Das had witnessed while campaigning—one thing stood out.

This time too, the state spared no effort in turning even basic demands, like clean air, into a hostile battleground, intimidating those who speak up and, even when forced to relent, keep the space hostile.

As pollution spreads and threatens more lives than the 2 million it already cuts short, the government's response has been to deny, distract and obfuscate as much as possible, which is why a clampdown on simple protests for clean air.

Das recounted the days after he first tweeted about the first 9 November protest: the number of police officials who called him, cops showing up at his home, and his decision to stay with a friend.

He had even anticipated an FIR.

“I thought they would register an FIR. I had already told my lawyers, please be ready. My own fear was that they would arrest me, or put me under house arrest, or illegally detain me,” said Das. “It was mentally distressing and would affect someone doing this for the first time.”

“The police are chasing and intimidating for what?” said Das. “For raising an issue peacefully. If there is a law and order problem, that is on them. What is their role?”

After the first November protest, around 80 people were briefly detained, and the police registered two FIRs against 30 people allegedly involved in a scuffle with the police and the recovery of pepper spray.

Things turned chaotic on 23 November when students allegedly used pepper spray and raised slogans supportive of Maoist leader Madvi Hidma, while the police registered FIRs for obstruction and assertions prejudicial to national integration.

The turnout was low, but the 3 December protest passed without incident. The government seemed to tread carefully. Heavy-handed action against a small air pollution protest would have looked bad—yet the police went to remarkable lengths to stop even these tiny gatherings.

Das recounted the frantic back-and-forth over the first protest on 9 November, when the police insisted the venue be changed from India Gate to Jantar Mantar, and the “bandobast”—the barricades, the Delhi police, the rapid action force.

“We decided we would stick to India Gate. This very idea of them giving us a spot to go and vent our anger. This does not make any sense. Why should we go to that one corner of the road where nobody comes, said Das. “It is the responsibility of the police to ensure the safety of peaceful protesters. All the great protests have taken place at India Gate, and it is the heart of Delhi.”

After the second protest on 19 November, 70 people filed RTIs (Right to Information applications) with the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) and the state Environment Pollution Control Committee (EPCC), for AQI data, monitoring reports, utilisation of funds and compliance data, demanding a reply within 48 hours under the life and liberty clause.

Das said they had not heard back.

“The dream is that it becomes something like the Anna movement, almost like a carnival at Janata Mantar or Ram Leela Maidan,” said Das. “People can come even after work. But to have those kinds of volunteers and resources is a humongous task.”

After Das’s tweet went viral, three WhatsApp groups with a 1000-person capacity filled up, he said.

But getting the word out wasn’t easy. Television media did not amplify the protests, though Das was pleasantly surprised that many dailies had covered them.

We spoke of the reasons why so few showed up: fear of protests and what the police might do, given the climate of intimidation over the years; memories of the CAA protests, the police linking the Delhi riots to them, and the farmers’ protests, and the routine threat of detention or FIRs.

Then there was apathy. Some who could afford to, including families with newborns, left the city and planned to stay away during the worst months. Those who were left behind had little choice.

There was also a sense that this was a problem too big to solve—like climate change.

On top of that, political and ideological divisions meant that mostly people from certain groups turned up.

Bridging these divides would take time, but it’s possible—after all, the protests weren’t about blaming any one party, Das was keen to emphasise.

“This is a bipartisan issue. It affects everybody. Every government has failed,” said Das. “The Supreme Court has failed.”

Still, the fact remains that the BJP is in power in Haryana, Delhi, and at the Centre, while crop burning in Punjab is reportedly at a seven-decade low.

That, Das believed, is what really angered people. Add to that the images of water being sprayed near AQI stations in Delhi that could distort the readings.

Not only were they doing nothing about the pollution, but they also weren’t even providing credible information for people to protect themselves to the extent they could.

After the first protest on 9 November, the government imposed stricter anti-pollution curbs, banning non-essential construction, limiting polluting industries and vehicles, while Delhi stepped up dust-control, road cleaning, and enforcement at construction sites.

The protesters are demanding a white paper detailing the pollutants, the steps already taken, the best practices that can be applied, and clear plans to reduce pollution.

Another striking part of the conversation with Das was what he shared about his conversation with the Delhi environment minister.

When Das said he suggested studying best practices from other cities, the minister shrugged it off, saying China wasn’t a democracy and that any steps here would get mired in protests, while cities like Los Angeles and London simply had smaller populations.

Das said that when he asked the minister whether there were any “visionary leaders” with the holistic understanding and technical expertise needed to tackle the issue, the minister seemed at a loss and simply kept repeating, “kya karein?”—what can we do? The minister too suffered from an air-related ailment that required two tablets a day, and had a child who, like Das, struggled with allergic bronchitis.

“There is no political will or political capital,” is what Das said he concluded.

To the media, the environment minister said, “Everyone, absolutely, has the right to protest. Through protests, the government becomes more conscious of its duties.”

Quite.

(Betwa Sharma is the Managing Editor of Article 14. This is a version of an editorial sent to subscribers.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.