Bengaluru: Santosh Kumar, a 41-year-old cab driver, registered on India's first national database for informal workers through the e-Shram portal in 2021. Launched in August that year by the union government, the website was meant to provide social security measures for India’s estimated 380 million unorganised sector workers.

Among the benefits promised were an accident insurance of Rs 200,000; the ease of accessing welfare entitlements, such as subsidised foodgrain anywhere in India; and inclusion of their names and locations on a database that union and state governments would use to deliver relief during crisis situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

One morning in April 2024, soon after Kumar dropped off a passenger at the Hyderabad airport, he suffered a heat stroke—Telangana was experiencing a heatwave that week—and had to be rushed to hospital where he spent a day.

The hospitalisation and other medical expenses set Kumar back by Rs 15,000, but he got no benefit from the e-Shram scheme, which had promised coverage under the Ayushman Bharat health insurance scheme.

“No one here knows the use of it,” he said, about his e-Shram card.

Advised to take a week’s rest subsequently, he did not venture out for a few days and lost a week’s income. He has an outstanding motor vehicle loan and family expenses, but found that the e-Shram registration had yielded no support from the government.

Like Kumar, tens of thousands who registered on the portal remain uncertain of what benefits will follow.

A Historic Move, With Little Effect

In August 2021, the government called e-Shram a “game changer in the history of the country”, the first-ever database for the “nation builders of India”, unorganised workers aged 16 to 59 years, whose details, including occupation, address, educational qualification, skill types and family details, would be in an Aadhaar-seeded database.

Instead of registering for a variety of union and state government social-security schemes, they could now benefit from all those on e-Shram.

“The e-Shram portal will cover all unorganised workers of the nation and help link them to social security schemes of the government of India,” then labour minister Bhupender Yadav had said. “The portal will prove to be a huge boost for the last-mile delivery of services.”

Three years later, however, workers said there is neither an implementation plan nor clarity on what social security measures will be extended to those who registered.

Article 14 spoke to around 50 informal workers, including some who had registered for e-Shram, from various occupations such as construction work, street vending, driving, gig work, work provided under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) 2005, belonging to Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Meghalaya and Delhi.

Not one could list the benefits of e-Shram.

Many from smaller towns had not heard of the scheme, while those in the metro cities were not aware of why they should register. Even those who had the card said they did not know how to use it.

Promising Launch

Ahead of the general elections in the summer of 2024, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) promised in its manifesto that it would reach out to migrant workers registered on the portal to empower them to avail benefits of various programmes.

“The launch of e-Shram was very promising,” said Dharmendra Kumar of the Delhi-based NGO Janpahal which works with informal workers. He said workers enthusiastically registered in the early months. “But the expectation of something concrete from the central government did not happen, and so the growth has flattened.”

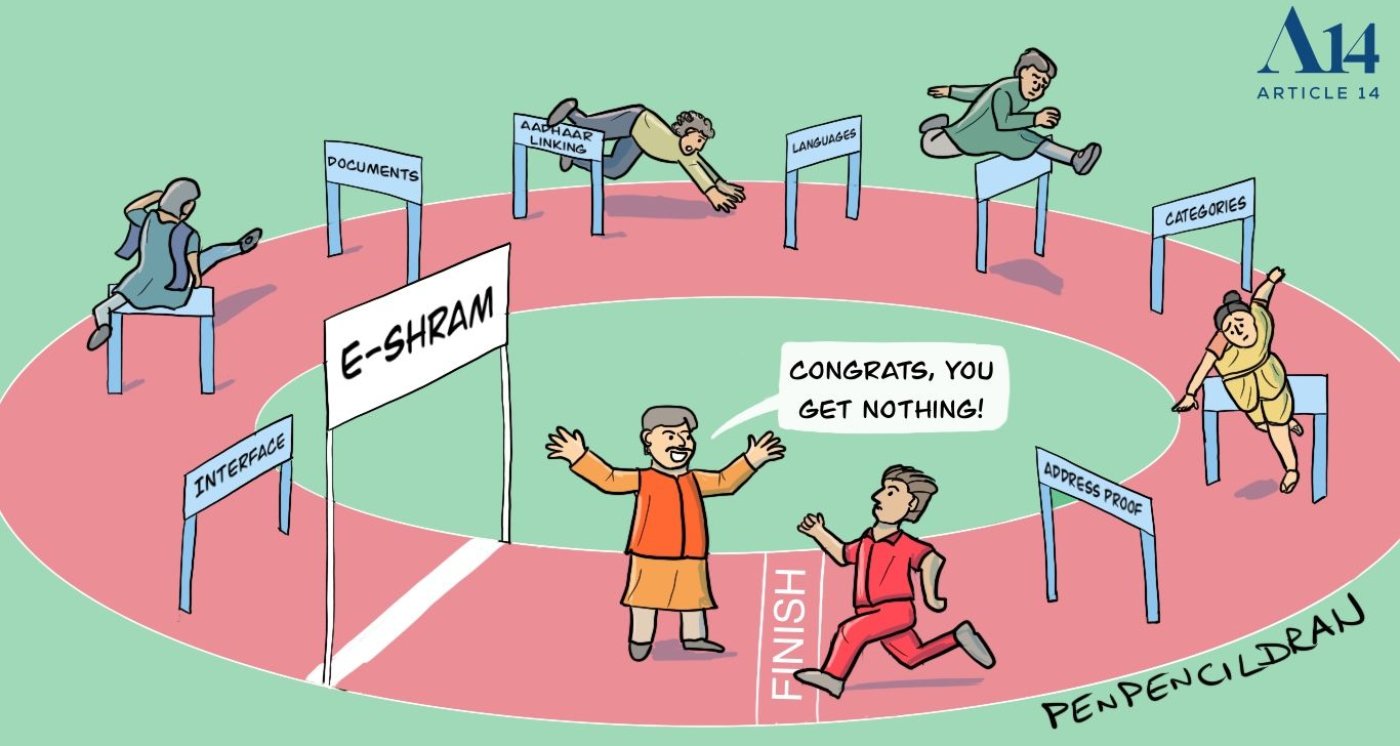

Experts said registering for e-Shram had been mired in difficulties—millions without Aadhaar would be left out of the system; migrant workers struggled to provide proof of address in the cities they work in; and the absence of clear benefits had led to registrations plateauing.

The responsibility to register workers, currently with the workers themselves, should be vested in the labour ministry or district-level committees, he said.

Weeks before the August 2021 launch of e-Shram, Sheikh Akbar Ali and his friends, all of them who work as contractual waste pickers employed, were invited to a government office in New Delhi. After the meeting, the workers beamed with joy. Ali said he was hoping that the e-Shram identity card would work like the MGNREGA job card, a tool to demand fair work and timely payments.

A native of West Bengal who has lived in Delhi for several years, Ali, 41, believed that a government identification would resolve a host of problems such as healthcare, and the lack of dignity that his community of garbage collectors has experienced.

In the following weeks and months, Ali, who regularly campaigns for the rights of waste pickers, got busy organising camps across the city to create awareness among informal workers to register on what is called the e-Shram website.

Now, three years after the launch, Ali is not interested in driving such campaigns and still does not know how an informal worker benefits from registering on the e-Shram portal.

A questionnaire e-mailed to the labour ministry did not elicit a response. E-mails were sent twice in July to the joint secretary and the director of the media cell of the labour ministry, and again in the first week of September 2024. These emails remain unacknowledged.

Slowing Registrations

The government’s target was to register 380 million informal workers. According to the website, more than 299 million, or 78%, of India’s informal workers have registered till date.

The target of 380 million may be an underestimation of the strength of India’s informal workforce.

According to the Azim Premji University’s State of Working India report for 2021, India’s informal workers numbered around 415.6 million in 2018-19, or about 90% of all workers in India. The study found that the pandemic had increased informality of workers.

According to the Economic Survey of India, India had 439.9 million informal workers in 2019-20.

Registrations on the e-Shram portal peaked in 2022 but plateaued subsequently. Several states and union territories, including Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Nagaland, Sikkim and Puducherry, showed tepid growth in the number of registrations over 2023.

For instance, Kerala, which achieved 59.08% of its target with 5.9 million registrations by March 2023, added just about 75,866 registrations over the last 15 months till August 2024. Similarly, Maharashtra till date has registered less than 50% of its target, or about 15.2 million instead of 34.48 million.

Experts said the slowdown in registrations reflects workers’ belief that the scheme lacks a clear mandate or benefits. Some also cited limitations of the portal itself, including common issues while registering, such as glitches with the mandatory linking of mobile numbers with Aadhaar, language barriers, the need for self-registration or reliance on common service centres (CSC), and a categorisation that many workers do not easily fit into.

The union government had said that it will integrate several schemes, such as the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY) or the national medical insurance programme; Ayushman Bharat, another health insurance scheme; MGNREGA or the workfare programme, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, a subsidy scheme for affordable housing; and ration card data for subsidised food under the public dIstribution system.

Impressive as this appeared, workers and experts told Article 14 that few of these benefits were in evidence for those who registered on e-Shram.

Informal Workers, Migrants Struggle

On 19 March 2024, the Supreme Court directed state governments and union territories to issue ration cards to 80 million migrant and unorganised workers under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013 within two months, stating that though these workers were registered on the e-Shram portal, they did not possess ration cards. However, even after four months, barring Tripura and Bihar, none of the other states and UTs has completed the exercise.

According to the e-Shram website, the five states with the most number of registrations are Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra while workers from agriculture, domestic and construction sectors are the most registered occupations.

Experts said that states such as Uttar Pradesh recorded higher registrations because people were promised (here) a cash transfer of Rs 1,000 if they registered. This was ahead of state elections in January 2022.

On 16 July 2024, the Supreme Court warned of contempt-of-court action against such states, and cautioned that chief secretaries of those states may be summoned.

“Why could the verification be not completed in four months… After four months you are still doing it and have the audacity to say another two months are required,” the bench said, directing that the verification, in order to grant migrant workers ration cards, be completed in four weeks.

Meanwhile, at the 112th International Labour Conference in Geneva on 4 June 2024, the ministry of labour & employment reiterated the e-Shram portal is a comprehensive database that would provide access to various social security programmes.

Informal workers who are migrants in urban areas may lose out on benefits announced by both, their home and destination state governments. For some schemes, documents that show proof of local domicile are required, but many fear to change their addresses.

Ali who works with migrant workers from West Bengal and the north-eastern states, said workers from these regions are often reluctant to change their address in fear of the implementation of Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019.

As per the Report On Migration in India of 2020-21, released by the ministry of statistics and programme implementation (MoSPI), the total migration rate in India was 28.9% and in rural areas was 26.5%.

Registering Is Not Easy

Ansar Ali, 50, who lives in Delhi has been unable to register on e-Shram as he does not have an Aadhaar-linked phone number. Ansar Ali said that after failing to register once, he was not keen to register since there seemed to be no benefits.

“No one has come to explain the process or how it would benefit us,” he said.

To register on the portal, workers need to provide their Aadhaar number, mobile number and bank account details. Upon registration, they receive a Universal Account Number (UAN). The portal also collects information about the workers, including their name, permanent address, current address, occupation, educational qualifications and skill type.

Workers registered on e-Shram are supposed to receive a pension of Rs 3,000 per month after 60 years, death insurance of Rs 200,000 and financial aid of Rs 100,000 if the worker suffers a partial disability.

Difficulties in registering have persisted since the launch, with many finding the mandatory Aadhaar-linked phone number a key hurdle.

Delhi-based Shalaka Chauhan who works with migrant workers said that to register on e-Shram, migrant workers need to have a smartphone and Internet connectivity.

“In cities, NGOs and middlemen at common service centres (CSC) assist these workers. In smaller towns, awareness is lower,” she said. Many also do not have Aadhaar cards linked to bank accounts.

Women informal workers, particularly, lack adequate documentation to register. Chauhan said where families use a single mobile phone for a whole family, they may find it difficult to link the number with Aadhaar.

The website has a long list of codes that are confusing, said workers. Though there are nearly 400 occupation codes, the categorisation is not clear, adding to the woes of registering.

“The interface is quite complicated,” Chauhan said. Also, the site was launched in English, and while Hindi was added, it is still not available in other regional languages.

Dharmendra Kumar said for instance, street vendors did not know if they were categorised as organised retail or if there was a separate code for them.

“There is no verification done of these registered workers and there are no visible benefits for them as of now, except that they have an identity card,” said Ravi Srivastava, director of the Centre for Employment Studies at the Institute for Human Development, a research institute in Delhi.

Delay ‘Unpardonable’: Supreme Court

In 2018, the Supreme Court has ordered chief secretaries of all states to begin registering India’s unorganised workers, in response to a petition filed in 2012.

In June 2021, the Supreme Court said the delay in setting up this portal was “unpardonable” and reflected a “lackadaisical attitude” by the ministry of labour and employment.

In May 2023, Article 14 reported that although the e-Shram database was created after the court pushed a reluctant union government, the website did not let migrant workers register alternative addresses, preventing them from accessing subsidised food and other promised benefits.

Srivastava said that the SC order in 2021 had aimed to safeguard circular and seasonal migrants.

However, the current method of data collection on the portal does not clearly account for migrants who typically have two addresses—one in a native village and another in their city of work. Instead, the portal only records workers who have relocated from one state to another.

Upon the launch of the e-Shram portal, the Working People’s Charter (WPC), a coalition of organisations working on issues related to labour, had issued a statement welcoming the move. They said it was acknowledgment of the long-standing view that policymakers needed reliable data on the informal economy, its workforce and patterns of migration.

Such a database would give informal workers an identity, and it could “prove to be effective in providing informal workers with much-needed social security entitlements,” it noted.

Unionists said, however, that their estimates of India’s unorganised workforce were much larger than the government’s conservative target for e-Shram registrations.

‘No One Here Knows Its Use’

“What is that?” asked a Hyderabad-based gig worker when Article 14 asked if she had registered on the e-Shram website. The woman requested not to be identified for fear of repercussions from her employers.

Many gig workers like her with different platforms made similar comments when asked about their registration on the portal.

According to the Economic Survey 2024, the total number of gig workers in India is projected to reach 23.5 million by 2029-30, up from 7.1 million in 2020-21.

Shaikh Salauddin, president of the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union, who helped many drivers like Santosh Kumar to register, said the government should ask cab aggregators to nudge drivers. “Or they should come forward through NGOs or other organisations and ask the drivers to register,” Salauddin said, “otherwise it is not possible.”

On 1 September, union labour minister Mansukh Mandaviya said the government would provide an online window for aggregators who employ gig workers to register them on the e-shram portal.

Experts said social benefits to workers through the e-Shram portal may not be possible right away.

Social welfare schemes have their own eligibility criteria and their own methods of verification. “So, a portal based on self-certification and where these eligibility criteria are not readily available will not work for the ministries that operate these schemes,” said Srivastava. He suggested that merging different databases would be another herculean exercise.

In the absence of a comprehensive migration policy, Srivatsava continued, there are gaps in social programmes designed for workers. “It’s all ad-hoc, some schemes have tried addressing the issues but overall there is no policy on migration,” he said.

(Sanghamitra Kar P is an independent journalist who writes on how technology impacts people for several national and international publications.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.