Updated: Jun 5, 2020

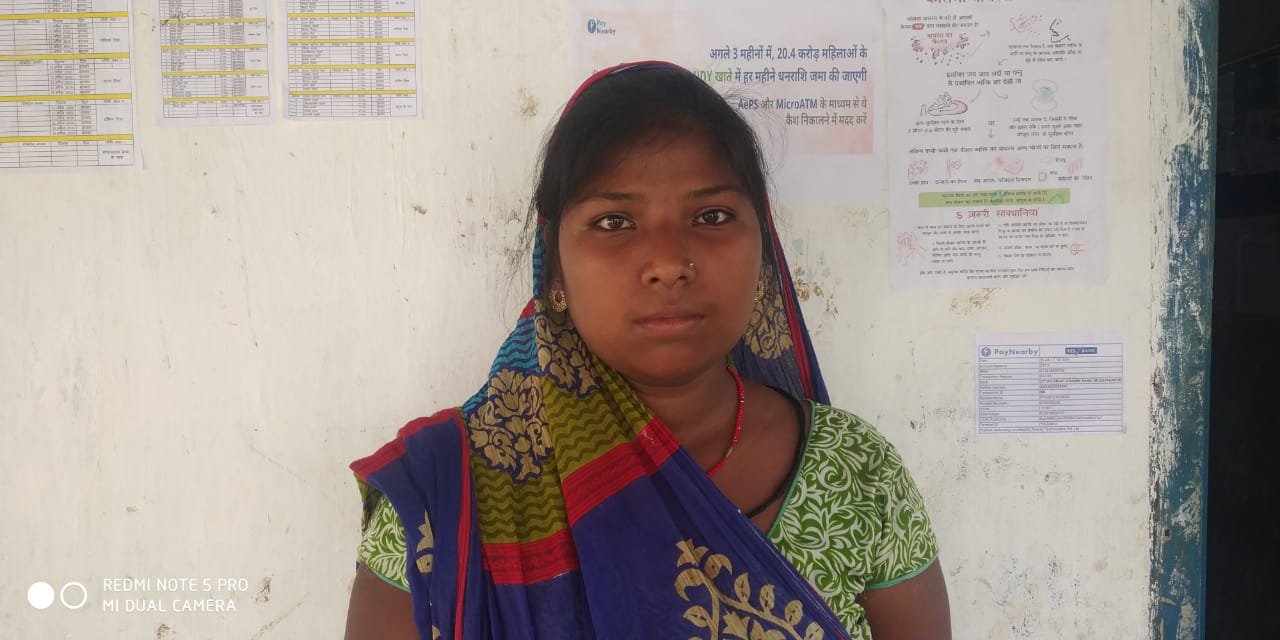

New Delhi: It has been more than two years since Manisha Devi, 35, applied for a correction in her ration card, the document that 814 million Indians officially classified as poor must have to get cheap food from the government.

When she was single, Devi shared her name on the ration card with her father. After marriage, when she sought a new ration card, she was disallowed from applying for a fresh one, since her name already existed on the old ration card.

“I’m tired of making the rounds for the (ration) card,” said Devi, whose husband is a daily wage labourer.

“Before the lockdown, I would find work in the fields, my husband would also find some work in the village,” said Devi from Pachkahar in Bihar’s West Champaran district. “In this way, we would somehow make ends meet.”

She said her husband and her had now taken a loan of Rs 7,000 from a local moneylender at an interest of 4% per month, “to make sure we have something to eat”. She is not clear how they will repay the loan.

“I don’t know how we will be able to survive this way,” she said.

Sikander Khwas, a Mumbai carpenter, lives in the same neighbourhood. He was visiting for a relative’s wedding when the lockdown was announced on 24 March 2020 as a public-health measure against the Coronavirus, leaving him unemployed.

Now in its second month, the lockdown has led to large-scale loss of livelihoods for India’s informal and migrant workers. Khwas neither has a source of income nor adequate food. He unsuccessfully applied for a ration card in 2018.

“I have made so many rounds of Narkatiaganj (the block headquarters) that I am tired now, but the card still hasn’t been made,” said 31-year-old Khwas, who borrowed Rs 5,000 from a relative to survive. “Once 10 of us even went to the block office, as well as to the village mukhiya (elected head of the village), but we were not heard. If only I had the ration card today, I would have been able to feed my family two square meals a day without depending on anyone.”

The COVID-19 shutdown has contracted India’s once-growing economy, pushing millions of vulnerable people closer to the edge. More than 131,000 had contracted the virus by 24 May in India and more than 3,800 were dead.

More than 122 million people lost their jobs in April, about 75% of them small traders and daily wage labourers, according to estimates from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a think tank, which said the rural job loss rate was 22.79% for the week ending 24 May. This unprecedented rise in unemployment has further stressed India’s struggling social-protection regime and heightened the precariousness of those who fall outside the food security net, said experts.

Early in the COVID-19 crisis, on 27 March, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitaraman announced that under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (Prime Minister’s Poor Welfare Scheme) 5 kg rice or wheat and 1 kg pulses (dal), would be made available free to ration-card holders for three months, in addition to what they normally collect. The government is now considering extending this free ration for up to three more months, the Times of India reported on 26 May.

On 2 May, Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Minister Ram Vilas Paswan said his government would ensure 3.9 million people—1.4 million in Bihar alone—without ration cards because of “inclusion errors” would also benefit from Sitaraman’s announcement.

“We are ready to meet all additional foodgrain requirements,” Paswan told the Hindustan Times. “We have enough stocks. Our aim is to ensure everybody has food.”

The lack of ration cards for people like Devi and Khwas are a result of the inclusion errors Paswan referred to. Their vulnerability increases as they borrow money to buy food. It is unclear if Paswan’s promise will deliver Sitaraman’s promised ration.

The Architecture of Exclusion

According to the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013, all families falling below the poverty line get foodgrain at subsidised rates. As per the NFSA, the Public Distribution System (PDS) is supposed to cover 75% of the population in rural areas and 50% in urban areas, which is 67% of the overall population (using rural-urban population ratio as per the 2011 census).

Calculations by economists Jean Dreze, Reetika Khera, and Meghana Mungikar show that using census 2011 data as the basis for calculating food security eligibility has left 100 million eligible individuals—the equivalent of the population of Egypt—outside the food safety net.

Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have the widest gaps, with an estimated 28 million and 18 million outside food security coverage, respectively. In many cases, new ration cards are not issued since the numbers stand saturated because of the 2011 census.

However, Minister for Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution Ram Vilas Pawan said on 23 April that the NFSA is supposed to cover only 710 million nationwide, of which 3.9 million receive no benefits because they have no ration card. Out of this 3.9 million, Bihar accounts for 1.4 million. The probable reason for this discrepancy is the Centre’s unwillingness to use updated data of the population to calculate state-wise NFSA coverage. If the Central Government is counting on the 2021 census data, that could be delayed due to the pandemic.

Many migrant workers have had their names removed from the ration card list as they left their villages for work, said Siraj Dutta, who is affiliated with the Right to Food Campaign, an advocacy. Ration cards are deactivated if beneficiaries have not purchased essential commodities for three consecutive months.

As they return home amidst the lockdown, this erasure is becoming the cause for their exclusion. According to many families, the process for applying for a new ration card is complicated and often protracted.

“Even after having applied for one, there is hardly any progress on getting a ration card,” said Dutta. “In Jharkhand alone, 700,000 cases are buried in government files. People depend on e-governance centres to make applications, but due to the lockdown, reaching these centres is difficult. And, in rural areas, the lack of banks makes these centers even more crowded.”

These centres, also known by unique state names, such as Pragya Kendras in Jharkhand, are physical facilities that deliver government of India e-services to rural and remote locations where access to computers and Internet is negligible.

However, persistent bottlenecks often prevent smooth public-service delivery through such centers, IndiaSpend reported on 25 November 2019. Mahmood Ali, who runs a Pragya Kendra in Tigri, a village in Ranchi district of Jharkhand, said that the government, often, does nothing for up to six month after receiving a ration-card application.

“People have to keep visiting the learning centers to find out if any progress has been made,” said Ali. “Sometimes the applications are stalled for months either at the block level or district office.” Reasons can include technical and biometric issues, crowding and store shutdowns.

Technical issues, particularly with Aadhaar—a 12 digit unique number assigned to all Indian residents—have significantly constrained access to ration cards, argued Reetika Kheera and Anmol Somanchi, associate professor and research associate at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad.

“It (Aadhaar) excludes people in three main ways: cancellation of cards (or names on ration cards) if people do not have an Aadhaar number, if they fail to link it with their ration card, and failure of the Aadhaar-based biometric authentication at the time of purchasing grain,” they wrote on 25 April in Economic and Political Weekly.

During the pandemic, many states have stopped providing rations through biometric authentication as a public health and safety measure, switching to one-time-passwords delivered to registered mobile numbers. However, individuals have been denied rations because they do not currently use the mobile number registered with Aadhaar.

A woman in Uttar Pradesh’s Badaun district died while waiting in queue for two days to receive her ration, according to BBC Hindi. The postmortem report has not been released, but officials suspected that she died of a cardiac arrest.

People Might Die of Starvation First

“In general, the process of making a ration card has always been complicated; (in the current scenario) there is no time to be lost in applying for a new ration card and to then determin(ing) who is eligible and who isn’t,” said Dipa Sinha, assistant professor of economics at Ambedkar University. “The government needs to ensure that anyone with documents that proves one’s identity should be granted ration.”

Some states, such as Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Delhi have done so but have made the Aadhar number mandatory. “Amidst this pandemic, they should make any document of identity enough to qualify for ration,” said Sinha.

“The central government should provide the state governments with rations, since ration is rotting in the warehouses of the central government and after the rabi (winter) crop there will be a need to buy more ration,” said Sinha. “State governments don’t have enough money to buy and deliver both themselves”.

Starvation and malnutrition have always been endemic issues in India—they account for 68% of deaths of children under the age of five—and the socio-economic conditions caused by COVID-19 exacerbate these vulnerabilities. The mid-day meal system is currently unavailable since schools have closed, as have anganwadis, childcare centres that combat hunger and malnutrition, leaving pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under the age of six the food and nutrition that they were entitled to under the Integrated Child Development Services Scheme.

The Supreme Court of India ordered the distribution of nutritional food to qualifying constituents through the home delivery system during the lockdown in a notice issued on 18 March 2020 to the Centre, states and union territories.

“While dealing with one crisis, the situation may not lead to the creation of another crisis,” the court order said.

It is doubtful that this public-service delivery system will operate at full capacity during the lockdown. In Bihar, for instance, 66.4% of those eligible for mid-day meals did not receive anything from anganwadis; the corresponding figure for Madhya Pradesh was 49% and Jharkhand 39.7%, News18 reported on 20 April.

Vandana Prasad of the Public Health Resource Network, a group of researchers, said India’s healthcare system “is not very good” but a lack of food worsens the situation. “If we don’t make other arrangements along with ration,” said Prasad, “People will die of disorganization more than from the virus.”

(Asheef Iqubbal is a research executive at New Delhi’s Digital Empowerment Foundation, which works on digital development, access, and digital rights.)