Delhi: More than four years and six months after the Delhi police filed a case in which they accused Umar Khalid and other activists who protested against the Citizenship Amendment Act for planning the riots in northeast Delhi, the case is not close to being tried.

Today marks four years since Khalid was jailed in connection with the “larger conspiracy case” registered under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967, a counter-terrorism law that restricts the right to bail.

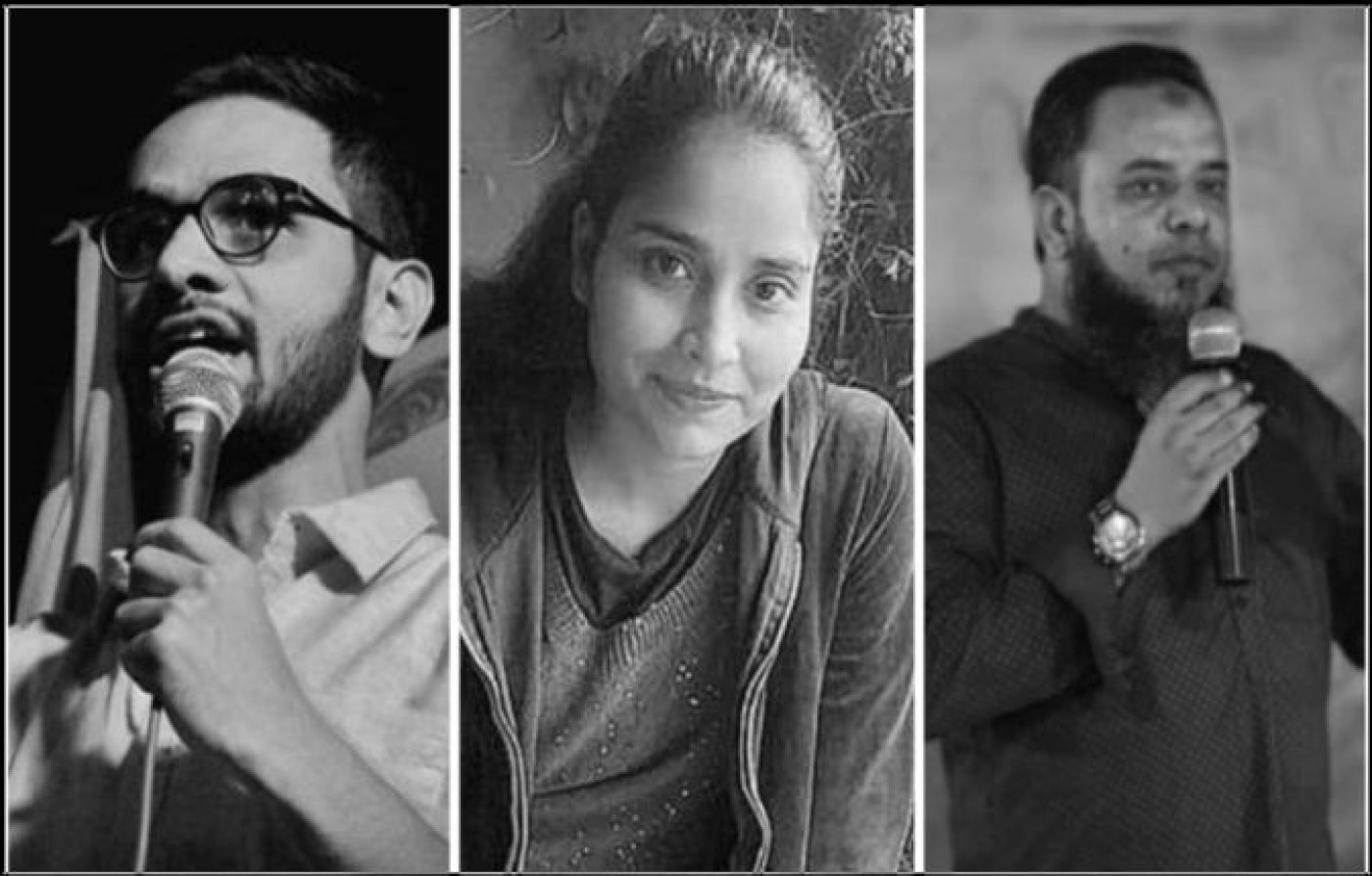

Twelve of the 18 accused have been jailed even longer without a trial, even though the Supreme Court has repeatedly said that bail, not jail, is the rule, as Article 14 reported earlier this month. Activists like Khalid Saifi and Gulfisha Fatima have been jailed for more than four years and five months.

Of the 18 chargesheeted in FIR 59 (first information report) of the Delhi crime branch, 16 are Muslim.

Three-quarters of the 53 people killed in the riots from 23 to 26 February 2020 were Muslim.

Judge Orders Framing Of Charges

On 4 September 2024, additional sessions judge Sameer Bajpai ruled that the prosecution had to inform the court if the police had finished investigating those accused in the “larger conspiracy case” of the Delhi riots case and were ready to frame charges.

With this order, Judge Bajpai allowed the contention of some of the lawyers in this case that four years after the police filed the first charge sheet and followed it up with four more—the last one in June 2023—the prosecution must say if the against the accused were complete and only then would they argue on framing of charges.

Framing of charges is the legal proceeding before the trial, where the prosecution and defence argue over whether the accused should be charged with the crimes mentioned in the chargesheet.

In light of the single-minded focus of pinning the riots in February 2020 on the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the suspect and motivated way the State had conducted itself in mounting the case, the chief concern that some lawyers had was that the prosecution would hear their arguments and then manufacture evidence to improve the case against their clients.

Several Delhi sessions court judges have at various times described investigations into the Delhi riots conspiracy case as “absolutely evasive,” “lackadaisical,” “callous,” “casual,” “farcical,” "painful to see,” and “misusing the judicial system”.

Over four years, judges have dismissed at least 60 Delhi riots cases, the latest in March 2024. One judge said police statements were “artificially prepared,” as Article 14 reported in May 2024.

“The level of ill intention is so much,” said one lawyer, speaking on the condition of anonymity. The prosecution is highly malicious and incompetent.”

Investigations Closed

The law on the completion of an investigation is section 173 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), which says a police report (chargesheet) has to be filed when the investigation is complete. This suggests that the legal requirement is that the state cannot file incomplete chargesheets.

The same provision says that filing the police report does not preclude further investigation if there is further oral or documentary evidence.

Special public prosecutor Amit Prasad has argued that the law does not require him to close the investigation before framing the charges and that some of the lawyers were trying to delay the framing of charges so that others could get bail.

However, Prasad’s final submissions on 28 August made it easier for Judge Bajpai to give the order directing the prosecution to inform the court whether the investigation against the accused was complete and if the framing of charges could begin.

While reiterating that there was no legal basis for the defence to demand such a thing from the prosecution, Prasad conceded that the investigation against them was finished.

Still A Long Way Away

More than a year after additional sessions judge Amitabh Rawat said the hearing on points of charge would be conducted daily, this crucial proceeding has been reached.

However, with four sections of the UAPA, 24 sections of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, two sections of the Public Safety Act, two sections of the Arms Act, and 18 people chargesheeted, this process could take considerable time.

In other words, more than four years after it was registered at the Delhi crime branch on 6 March 2020, the trial is nowhere in sight. Furthermore, a trial with 18 accused, thousands of pages of chargesheets, over 100 witnesses, and multiple lawyers who would cross-examine could also take many years.

In recent orders, the highest court has said that when incarceration violates the right to life and liberty, which includes the right to a speedy trial, then the bail, not jail, rule applies to even those cases registered under terrorism and money laundering laws that have more stringent bail conditions.

These precedents, however, don’t seem to apply to those accused in the conspiracy case, which holds the activists behind the anti-CAA protests responsible for the riots.

To do this, the police have built a case on inferences, conjectures, partial truths and falsehoods.

Regular activities in a public movement are painted in a sinister light. Witness statements are the same, all vilifying the protests and protesters. Some are demonstrably unreliable, and others are improved upon from one statement to the next.

There is nothing illegal about Khalid's speech in Maharashtra a few weeks before riots erupted in Delhi. That speech had troubled the police more than the incendiary one that a leader of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) made in northeast Delhi a few hours before the riots erupted in the area.

Yet, the accused remain behind bars as their hearings are adjourned month after month, year after year.

When judges are transferred and move on with little thought to the lives of the people in the balance, the hearings have to be heard afresh.

Khalid’s bail has been rejected twice by the district court, once by a division bench of the Delhi High Court, which includes a judge who, while giving bail to three of his co-accused a year earlier, did not find any prima facie case against them and said that state had blurred the lines between terrorism and the right to protest to crush dissent.

Despite its precedents prioritising life and liberty, the Supreme Court did not hear Khalid’s bail case in the nine months it bounced from one judicial bench to another.

It Has Happened Before

Some lawyers wanted the prosecution to definitively declare the case against their clients closed because they feared that once they began arguing on charge, the prosecution would use what they argued to plug loopholes and improve their case.

These fears were not unfounded, given that the police did the same in another case we reported last year, which dealt with the violence that followed a protest outside Jamia Millia Islamia University on 13 December 2019.

After it emerged during arguments on charge that there were no eyewitnesses to identify at least five of the 11 students accused of rioting and being part of an unlawful assembly, the police filed a fourth chargesheet, which had eyewitnesses who claimed to have identified them. They filed a day before the conclusion of the final arguments.

Discharging the 13 accused in February 2023, Verma said, “During the course of arguments, the question of nonidentification of accused by police witnesses was raised, and ostensibly, to fill this lacuna, the present chargesheet has been filed.”

“….there were no eyewitness confirming their presence on the spot. It is only in the third supplementary chargesheet that witnesses have identified them,” Verma said.

“In the present case, it has been most unusual of the police to file one chargesheet and not one but three supplementary chargesheets, with really nothing new to offer. This filing of a slew of chargesheets must cease, else this juggernaut reflects something beyond mere prosecution and would have the effect of trampling the rights of accused persons,” Verma said.

Delhi High Court Precedent

Justice Swarna Kanta Sharma of the Delhi High Court reversed the discharge and sent it back for trial, saying that at the state of charge, the court could not question the veracity of statements of public or police witnesses.

However, Sharma also considered the concern about the prosecution hearing the arguments on charge and then filing another chargesheet to “fill in those lacunae” and whether the investigating agency had to put down the “entire investigated material” before the arguments on charge.

Sharma said the court could ask whether a chargesheet was forthcoming before proceeding with the arguments.

“...this Court also holds a view that at the stage of framing of charge, the Court may put a question after filing of the chargesheet and before hearing arguments, and the prosecution will inform the trial courts as to whether the case was ripe for hearing arguments on charge and as to whether the chargesheet has been finally filed against the accused, against whom a Court is proceeding to hear arguments on charge,” Sharma said.

Relying on this precedent, Bajpai, the Delhi riots conspiracy case judge, said, “...prosecution must inform the court if the chargesheet has been finally filed and the case is ripe for hearing arguments on charge.”

New Evidence

The FIR for the Delhi riots conspiracy case was registered on 6 March 2020, and the UAPA provisions were invoked on 19 April 2020.

The first chargesheet was filed on 16 September 2020, and four more followed on 22 October 2020, 23 February 2021, 2 March 2022, and 7 June 2023, three years and three months from the date of the FIR. However, the police said the investigation was continuing.

While noting that section 173 (8) provided no restriction on filing chargesheets, Bajpai said the law also said supplementary chargesheets could only be filed “with regard to the material or evidence which is collected afresh and not on the basis of the evidence which is already there in the possession of the investigating agency”.

In this case, lawyers said the police had seized their phones when they arrested the accused, and with each successive chargesheet, they rely on a new aspect of a chat or a location, material the police have for over four years.

Exculpatory Material

Some lawyers have also asked the prosecution to give them all the documents containing exculpatory material, which is not placed in the chargesheet but may favour the accused.

For instance, witnesses who say the accused were protesting peacefully.

So far, the prosecution has said they cannot supply the complete documents because the investigation is still pending.

Lawyers had said they can only be expected to argue on charge once they have the complete list of documents.

A Matter Of Strategy

It is worth mentioning that only a few lawyers of the 17 accused asked the prosecution to disclose whether the investigation against their clients was closed before they proceeded to arguments on charge.

Umar Khalid, for instance, has not.

Most of the lawyers did have clients who were already out on bail.

It boils down to strategy, which varies from person to person and the specific allegations against their clients.

Some lawyers, for instance, feel the case against their clients is so poor that they can discharge them at the stage of framing charges even before the trial. Others want to get to the trial so they can prove their innocence.

With the court order making way for arguments on charge, there is more urgency to get bail because once charges are framed, it will become more difficult to get bail.

Framing of charges means that a case is prima facie true, and under section 43D (5) of the UAPA, this is a condition for denying bail.

Context For Concern

For the Indian police to carry out shoddy investigations and even frame individuals is a sad reality that plagues the justice system, and defence lawyers are routinely concerned about the quality and intent behind the chargesheets they file.

In the Delhi riots cases, however, these fears are accentuated by the demonstrable falsehoods and bias that mar both the substantive and procedural aspects of the investigation and the prosecution.

The Delhi riots conspiracy case, which pins the blame for the riots on the anti-CAA protests and those involved in the protest, is not just a criminal matter but a case with political significance to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government that opposed the anti-CAA movement and was stunned by how long it sustained despite a vilification campaign by the pro-establishment media and many right-wing leaders and groups.

The movement saw many activists emerge at a time when the government had stifled freedom of speech and expression since coming to power in 2014.

Khalid, in particular, was a well-known critic who many in the Muslim community looked up to as a symbol of resistance at a time of unprecedented anti-Muslim radicalisation and Islamophobia.

In light of this background and the improvements made to the chargesheet in the Jamia violence case, lawyers in this conspiracy case feel the prosecution cannot be trusted to play fair.

The police have shown itself to be petty and malicious.

Three years ago, they refused to provide hard copies of the first 17,000-page chargesheet to the accused, saying that they had discharged their duty by handing over the soft copies on pen drives and that they did not have the money to print thousands of pages.

In this case, the accused and the lawyers are from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, with varying degrees of comfort regarding virtual meetings and soft copies.

“All these things are not happening in a classroom or an academic discussion,” said a lawyer. “They are happening in real life with people's lives at stake.

(Betwa Sharma is the managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.